This is a guest post by Mario Asselin. Mario Asselin is the founder of The AirCraft Company and a co-founder of Asselin Inc. With over 40 years of experience in aircraft performance, flight test, and certification, he has worked across commercial and regional aviation programs globally. He is based in Kansas and writes from direct experience with the erosion of regional air connectivity.

For decades, regional aircraft have been marketed and debated largely on a single headline metric: range. How far can it fly? How much farther than the previous model? How close does it come to mainline jet capability?

That framing has outlived its usefulness.

In practice, the fate of regional air service is shaped far more by economics at the short end of the network: break-even risk, cost variance, and the ability to sustain frequency on thin routes. These factors, not maximum range, determine whether a community keeps air service or quietly loses it.

Recent analysis has highlighted that legacy regional designs struggle to reach today’s operational “sweet spot.”[1] The deeper issue, however, is that the sweet spot itself is moving, and conventional aircraft architectures are structurally unable to move with it.

Where Regional Flying Actually Happens

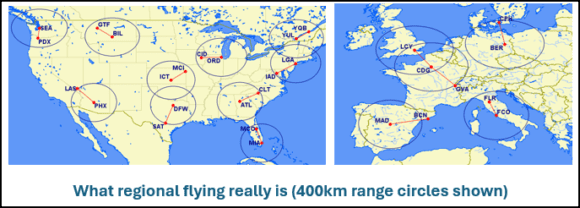

Observed airline behavior is remarkably consistent across geographies.

Departure-frequency data show that the highest concentration of regional flying occurs on routes well under 300–400 kilometers. These are the distances that support day-return business travel, medical and government mobility, and schedules built around frequency rather than capacity.

Longer regional sectors certainly exist, but they represent a much smaller share of departures. In other words, most regional flying is short flying.

And yet, these are precisely the routes that have been disappearing.

Regional Airline Association data illustrates the pattern clearly:

- Average load factors have climbed steadily toward ~80%

- Aircraft gauge has increased

- Frequencies on short routes have been reduced or eliminated

This is not a demand collapse. It is a risk response. Airlines have adapted to aircraft that punish short stages by reducing exposure (fewer departures, larger aircraft, and longer average stage lengths).

Minimum Economic Range: the Hidden Variable

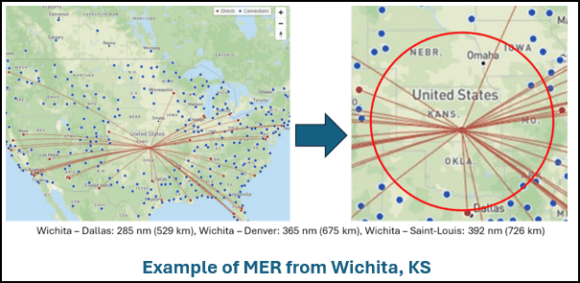

A useful way to understand this dynamic is through the concept of the Minimum Economic Range (MER) [2].

MER is the shortest stage length at which a given aircraft can operate profitably at realistic load factors. Below this distance, the fixed and semi-fixed costs of each departure overwhelm the revenue opportunity.

Crucially, MER is not fixed.

For conventional turboprops and regional jets, MER has been creeping outward over time due to several reinforcing effects:

- Aging technology

Most aircraft serving the 30–90 seat segment today were designed around propulsion and systems technology dating back several decades. While large commercial turbofans have benefited from sustained investment in efficiency, small gas turbines have seen far more limited gains. - Flattening efficiency curves

Gas-turbine thermal and propulsive efficiency improvements exhibit strong diminishing returns at smaller scales. Incremental advances no longer offset rising fuel prices, maintenance costs, and cycle-driven wear. - Short-stage cost dominance

On short routes, climb energy, crew cost, maintenance cycles, taxi fuel, and delay exposure dominate economics. Ownership cost matters less than cost per departure, and that cost has been rising.

The result is an expanding economic vacuum around many regional airports: destinations that are geographically close but economically unreachable by air. Communities are not unserved because they are distant… they are unserved because they are too close.

Why Legacy Aircraft Cannot Move the Sweet Spot Back

Much of the current debate focuses on whether there are “enough” 50-seat regional jets left to serve future needs, or whether turboprops can reclaim share from jets.

This misses the structural problem.

Even when capital costs are low, legacy regional aircraft carry:

- High variable cost per departure

- High sensitivity to fuel price and maintenance escalation

- Poor economics in idle, taxi, and delay regimes

- Break-even load factors that force conservative scheduling

Up-gauging to 70–76-seat aircraft improves pilot productivity, but it raises risk on thin routes and pushes airlines toward fewer daily frequencies. The network becomes more brittle, not more resilient.

Frequency, Weather, and Network Fragility

Reduced frequency does more than inconvenience passengers; it fundamentally changes how regional networks respond to disruption.

On routes served only once or twice per day, even modest weather events can eliminate all service for an entire day. A morning cancellation due to fog, crosswinds, or convective weather often cascades into missed aircraft positioning, crew-legality constraints, and a lack of spare lift to recover later departures.

By contrast, higher-frequency networks inherently absorb disruption. Later flights provide recovery opportunities, aircraft and crews remain closer to schedule, and passengers can often be reaccommodated the same day.

In many regional markets today, the dominant weather risk is no longer turbulence or icing… it is the absence of a second flight.

As regional networks have thinned, weather resilience has quietly eroded. Communities that once experienced delays now experience full-day outages. The operational risk of weather is no longer spread across the schedule; it is concentrated into a single point of failure.

This fragility is most acute at short-runway and secondary airports, where weather margins are tighter, diversion options are limited, and a single cancelled departure can effectively disconnect a community for the day.

What Kind of Architecture Can Arrest the Drift?

If the problem is structural, the solution must be architectural.

To move (or even hold) the regional sweet spot in place, an aircraft must do more than reduce average cost. It must flatten the breakeven curve, reducing the penalty associated with short stages and frequent departures.

That implies several design principles:

- Maximizing energy-path efficiency, not just cruise efficiency

- Eliminating “energy parasites” during taxi, idle, and delay

- Decoupling takeoff and climb power from cruise energy production

- Reducing cost variance, not merely cost averages

Electric propulsion, when used selectively and deliberately, introduces exactly these variables. The key is not full electrification for its own sake, but electric-first operation, with other energy sources engaged only when economically justified.

A Worked Example: Collapsing the Minimum Economic Range

One recent example of this approach is the Pangea® regional aircraft family developed by The AirCraft Company.

Rather than maximizing range, the design is explicitly optimized around short- and medium-haul missions, with electric-first operation handling ground operations, takeoff and initial climb, and approach, landing, and go-around reserves. Compact turbogenerators are used only as energy extenders during cruise when required, operating at steady, efficient power settings rather than cycling through high-stress regimes.

The economic consequences are significant:

- Direct operating costs on short routes are reduced by multiples, not percentages

- Break-even load factors on sub-250-mile missions fall into single digits

- High-frequency service becomes economically viable again

In effect, the minimum economic range collapses inward, reopening routes that legacy aircraft have already abandoned.

The important point is not the specific configuration, but the demonstrated principle: when the cost slope is flattened, behavior changes. Airlines can afford to schedule frequency instead of hoarding seats.

Strategic Implications

If this interpretation is correct, the implications extend beyond any single aircraft program.

For airlines:

- Scarce pilots can be deployed on higher-margin, lower-risk short routes

- Thin markets can be served with frequency rather than capacity

- Network resilience improves as reliance on marginal long-haul connections decreases

For policymakers:

- Regional connectivity can be restored without permanent subsidies

- Decarbonization and accessibility objectives align with economics rather than fighting them

- Short-runway airports regain relevance

Most importantly, this reframes the regional aircraft question. The goal is no longer to chase range parity with jets, but to design aircraft that tolerate short stages economically over decades, not just at entry into service.

Holding the Sweet Spot in Place

The regional aviation sweet spot is not static. Left unaddressed, it continues to move outward, quietly eroding connectivity even where demand persists.

Legacy aircraft cannot follow it. Incremental improvements are no longer sufficient.

Architectures designed around electric-first principles, low break-even risk, and short-stage economics offer a different path: one that does not merely adapt to the moving sweet spot, but holds it in place.

For regional aviation, that distinction may determine whether connectivity continues to contract or finally begins to recover.

[1] https://airinsight.com/the-regional-aircraft-sweet-spot-legacy-designs-cant-reach/

[2] https://www.linkedin.com/posts/mario-asselin-28b43423_electric-first-design-concept-activity-7251906030559744001-p7H1?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAATeb4sBL1wnBmgzvR1RoqJ8aOhJBbTsFR0

Views: 386