Mahan A346

Recently, we had news about Iran acquiring five 777s. It was the usual suspicious methods and trial of airplanes going all over and then disappearing from the ADS-B feeds.

Something does jump out, though.

Rolls-Royce

The Iranian 777s come with Rolls-Royce engines. The last widebodies Iran acquired, legally, were A330s with Rolls-Royce engines. Its suspicious acquisition of A340-600s came with Rolls-Royce engines. Is this a pattern that one might think tells a story? Or at least would highlight something to ask about?

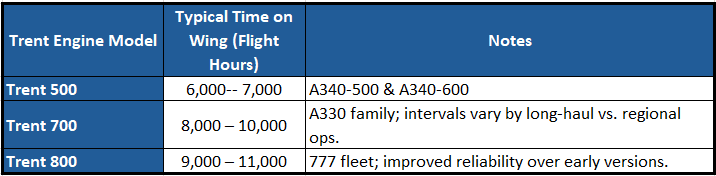

Take a look at this table and consider how often Iranian aircraft require a visit to the shop.

These engines need spares and maintenance. Engines account for 30–50% of total aircraft MRO costs over an aircraft’s lifecycle, often exceeding millions of dollars per shop visit. Engines have defined on-wing limits (hours/cycles) that require scheduled inspections, hot section checks, and complete overhauls.

Crucially, engine OEMs (Rolls-Royce, GE, Pratt & Whitney, CFM) dominate the MRO market with proprietary repairs, data analytics, and long-term service agreements (TotalCare or Power by the Hour). Over 80% of Rolls-Royce large civil engines in service are covered by “Power by the Hour” contracts. One can assume the Iranian engines are not in that 80%.

The Gray Market

How do Iran’s airlines handle their MRO work? Third-party brokers and middlemen in countries with loose export controls (Central Asia, Africa, or Southeast Asia) are often used to source components and engine parts. There have been reports of parts being rerouted through front companies or rebranded as “used” to bypass U.S. export restrictions.

There is speculation of technical cooperation with countries like Malaysia or Indonesia, where older MRO facilities have experience with out-of-production engines. One only has to follow the trials these aircraft have taken from their origin points to the time they disappear from ADS-B coverage and then miraculously appear in Iran. The countries involved before that magic moment have a role and a responsibility.

Legal Limits

Iran’s acquisition of aircraft is restricted by U.S., EU, and UN sanctions, primarily aimed at curbing access to modern aviation technology. The key laws and regulations include:

- U.S. Sanctions (Primary Restrictions)

ITSR (Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations): Administered by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), these prohibit U.S. persons and companies from selling aircraft or parts to Iran without a specific license. - U.S. Export Administration Regulations (EAR): Aircraft and engines with more than 10% U.S.-origin content require U.S. approval for sale to Iran, which impacts modern Airbus and Boeing aircraft.

- CAATSA (Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, 2017): Tightened sanctions on Iran’s aviation sector, targeting both Iranian airlines (like Mahan Air) and third parties supplying them.

- EU Sanctions

The EU restricts the export of aircraft and parts to Iran, particularly for dual-use items (both civilian and military). EU sanctions align closely with U.S. measures, often preventing Airbus deliveries (as Airbus aircraft have significant U.S.-made components). - UN Sanctions

UN sanctions related to Iran’s nuclear program were lifted under the JCPOA (2015), but after the U.S. withdrawal in 2018, U.S. secondary sanctions effectively reimposed restrictions on global sales. - Secondary Sanctions

Even non-U.S. companies face penalties if they sell aircraft or parts to Iran, as they risk losing access to the U.S. financial system.

The limits on Iran acquiring modern commercial aircraft are restrictive and thorough. Yet Iran keeps getting aircraft.

Iran acquires aircraft on the secondary market through brokers, often using shell companies in countries not fully aligned with U.S. sanctions (e.g., Malaysia, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, or African states). For example, aircraft are registered under flags of convenience (e.g., Madagascar’s “5R” prefix, used in 2025 for the recent ex-Singapore Airlines 777-200ERs) before being quietly transferred to Iranian carriers, such as Mahan Air. In July 2025, five ex-Singapore Airlines 777-200ERs reached Iran after being staged in Siem Reap, Cambodia, with their transponders disabled over Afghan and Pakistani airspace.

Sanctions? What Sanctions?

Several companies and individuals faced severe legal and financial consequences for violating U.S. and international sanctions by delivering or facilitating commercial aircraft sales to Iran. The U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) and other authorities have aggressively enforced these sanctions. Here are key examples:

- Mahan Air-Related Sanctions — Mahan Air, Iran’s second-largest carrier, has been under U.S. sanctions since 2011 for allegedly supporting the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and terrorist activities. Numerous companies, especially in the UAE and Turkey, have been sanctioned for leasing or transferring aircraft and parts to Mahan Air. For example, in 2019, Blue Airways and My Aviation Company (Thailand). Both entities were sanctioned for facilitating the transportation of aircraft and parts to Mahan Air. In 2017, Ukraine’s Dart Airlines and UM Air were sanctioned for providing aircraft to Mahan Air.

- Balli Group PLC (UK) — In 2010, Balli Aviation Ltd. (a UK-based subsidiary of Balli Group) pleaded guilty to violating U.S. export laws by leasing 747s to Iran’s Mahan Air. They were fined $15 million and placed on a five-year probationary period for their corporation.

- Sayegh Group (UAE) — In 2018, Sayegh Group Aviation was accused of assisting with aircraft transfers to Mahan Air and other Iranian airlines. The U.S. Treasury froze its U.S. assets and prohibited any dealings.

- Reza Zarrab (Turkey) — Primarily known for evading oil and gold sanctions, Zarrab’s network reportedly facilitated financial transactions linked to the procurement of aircraft parts for Iranian carriers. He was arrested and prosecuted in the U.S., eventually becoming a key witness in sanctions-related cases.

- Aircraft Brokers and Shell Companies — Several Malaysian and Armenian companies have been sanctioned for brokering the sale of used Airbus and Boeing aircraft to Iran through shell transactions. For example, in 2019, sanctions were imposed on Armenia-based Flight Travel LLC for arranging aircraft sales to Iran. In 2016, Al Naser Airlines (Iraq) was sanctioned for assisting Mahan Air in acquiring A340s and A320s.

- Aerospace Component Suppliers — Small European and Asian companies have faced OFAC blacklisting for shipping engine parts, avionics, or landing gear to Iran. For example, in 2020, China-based Dalian Sunny Sky International was blacklisted for shipping engine components to Iranian carriers.

Legal ramifications appear insufficient

U.S. penalties for sanctions violations can reach millions of dollars per aircraft. Criminal charges are also a consideration, as executives risk criminal prosecution, as seen with Balli Aviation. Then there is reputational damage as airlines or lessors caught in these deals are blacklisted globally, making future contracts difficult.

Yet here we are, another five aircraft whisked into Iran despite all the legal risks. The legal hurdles are insufficient. The costs of being caught don’t dissuade people, companies, or even countries.

With all these sanctions in place, it appears they’re not worth much. Can it be that the combined power of the UN, the EU, and the US is insufficient to prevent these aircraft and spares from getting to Iran? The need for spares is constant, yet they continue to arrive in Iran.

As the table above shows, Iran likes Rolls-Royce engines. Tracking spares from one OEM shouldn’t be hard. However, it appears that the combined authorities are unable to do so.

Views: 837

Your photo shows a Mahan Air A340-300, with CFM-56 engines. Not a Rolls-powered A340-600

OK, we switched it

It’s civilian aviation so making domestic flights safer, albeit much more expensive, for Iranians who are being squeezed from all sides internationally and domestically…

It’s fascinating to see how Iran’s fleet acquisitions impact the aerospace industry. The dynamics between Airbus and Boeing in this context are intriguing. Do you think this will lead to significant changes in the airline landscape?

The dynamics with respect to the Iran market reflect geo-political actions, including sanctions and trade restrictions, that impact the two OEMs. We are not experts in forecasting geo-political actions by either side in the on-going disputes, particularly given Iran’s recent declaration of a state of war with the US, Israel, and western countries. In such an environment, all bets are off and restrictions on planes and spare parts by both the US and France/Germany will be in place.