The US airline industry is amid earning season. The reported earnings and news have been great. Records are being broken. The pandemic is behind us. Pilots are getting 40% pay increases. Everything is rosy! Let’s talk about the news not being reported and the missed opportunities in ops costs that are swept under the rug. We noted earlier this week that US airlines do not have great time management.

The DoT says any flight arriving within 15 minutes is on-time. This a weird metric since airlines define their estimated arrival time in their schedules. But we digress. Here’s the percentage of US airline flights that arrived 15 minutes or more late over the past few years. The 2023 numbers are through April.

The total column on the right is the average for the airline over the period. The total row along the bottom is the industry average for the period. So, between 2017 and April 2023, the industry average for arrivals is 17.7% over 15 minutes. About every sixth flight arrives more than 15 minutes late.

If we eliminate 2020 and 2021 as pandemic years, the industry average goes from 17.7% to 10.3%. In other words, during the pandemic period, with fewer flights, there were fewer delayed arrivals, as queuing theory suggests.

Airlines are expensive businesses to run. Assets are very expensive, and the staff are highly skilled. So, these delays cost serious money – like telephone number sizes. The same total numbers apply here. Over the period, US airlines “ate” nearly $40Bn because of late arrivals using the DoT 15-minute grace period. The number is staggering. For those thinking about weather and other exogenous impacts, remember they impact all the airlines. Moreover, the industry is mature and has excellent weather forecast information.

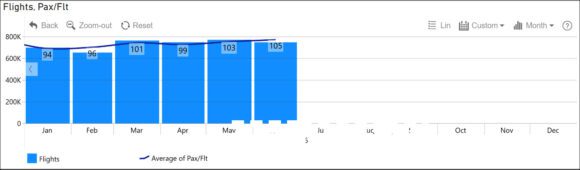

Look at the trends of the number of flights US airlines are performing and their 15-minute late arrivals. Sure, there are seasonality issues like the weather. But the number of flights arriving late after the pandemic is rising rapidly. From 2022 through April 2023, we are looking at over one in five flights arriving 15 minutes late.

It’s not all bad news, though. The following chart illustrates that the industry tries hard to catch up for lost time. Airlines know that time is money since that is what they sell. You burn more fuel to make up the time, but fuel is ~45% of your costs. You still save money by saving time.

The next chart shows the trend from 2017 through April 2023. Airlines try to catch up as the day nears midnight. Note schedule performance declines from about 5 pm.

There is a problem that warrants discussion is schedule padding. We define schedule padding as the number of minutes between the schedule and actual arrival.

The average padding is nine minutes, which one might consider irrelevant. It is not. The spike from the pandemic does through off the chart, but the other periods show a consistent trend.

Looking at ATL-BOS, we see that schedule padding moves around a lot. Note airlines enter and leave markets.

Here’s another example: DFW-ORD.

Schedule padding varies between airlines, as the next table shows. The pandemic threw schedules off. Overall, the amount of CRS time compared to actual time reflects each airline’s view of its operational capabilities.

Returning to the ATL-BOS example, look at the two tables tracking minutes. The data shows that operating airlines set the padding at an average of ~12 minutes in this market. Note the scheduled times are close but not identical. Spirit offers the shortest schedule, and its padding is tighter.

A lot of operational data on US airlines suggest that the great earnings being reported are, perhaps, not as good as they could be. The debate about who is to blame, FAA or the airlines, is moot – both have a share in this problem. Airline stockholders are bearing the financial impact.

This next series of charts illustrates this well. Airline costs have risen due to fuel cost increases and rising labor costs as the industry has been on a hiring tear as it recovers from the huge layoffs during the pandemic. These two inputs account for close to 75% of operating costs.

Airlines’ costs are rising sharply, and with pending pilot salary increases in the 40% range, they will keep rising. The operating cost/minute now averages $112. Average delayed arrivals are nearly 16 minutes, which means the estimated cost of the lost time is close to $46Bn through April 2023.

One might question this eye-popping number; after all, it is variable costs that are impacted by delayed arrivals – the extra fuel and labor costs. As noted, these two alone account for ~75% of overall operating costs. By that measure, the impact is not $46Bn but closer to $35Bn. Fair enough, that is a reasonable point. The impacts are quite broad; excess capital (aircraft, GSE, facilities), excess labor costs (direct, reassignment, and reserve), as well as latent utilization, and latent revenue, with market demand, competitive circumstances, and carrier response/strategy defining whether capital and cost reduction or stretch for utilization and revenue is most appropriate.

Both numbers are higher than what we show above using the 15-minute rule. The higher number reflects the performance against airline published schedules.

Shouldn’t Wall Street be asking about this? Reuters reports the global airline industry doubled its forecast for 2023 profits “but warned delays in getting planes to cope with rising demand could dampen their post-pandemic recovery.” The global industry expects to report $9.8 billion.

The $9.8Bn looks paltry when considering how much the US airline loses in missed schedules. Quibbling about if the real loss is $46Bn or $35Bn is small beer considering US airlines lose around three to four times global airline industry profits because of missed schedules.

Views: 30

Hi Addison, great report. I might be reading it incorrectly but the following quote suggests that eliminating the lower percentage years reduces the average percentage. I read the intent though as being if you only take those two years, the average drops to 10%? Either way though, loved the report. Thank you

“If we eliminate 2020 and 2021 as pandemic years, the industry average goes from 17.7% to 10.3%. In other words, during the pandemic period, with fewer flights, there were fewer delayed arrivals, as queuing theory suggests.”

I couldn’t get your table to average 17.7%. Could be some weighting in there but I got 18..8% with Hawaiian being digest disparity math wise. I couldn’t get to 10.3% either. It was the interest that your piece generated that made me want to look!

Hi Addison, I’d like to know if you are considering in the ops cost the fixed cost (salaries, aircraft rentals, maintenance)? In the example shown, How do you arrive to the $46Bn figure? Because if I consider

– Operating cost/minute now averages $112.

– Minutes delayed 15,8 min

– Qty Flights delayed 2 M (a little bit more)

The result is 112$/min x 15,8 min/vuelo x 2 M vuelo = 35,4Bn$

Why did you mention 46 Bn$ ?