DOT logo

We have been analyzing and publishing data models based on U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) datasets for several years. This experience has given us some confidence that we understand the various datasets. We feel comfortable with the data rhythms, if you will.

Imagine our shock after a recent visit to the DOT to discuss a glaring issue. We identified a problem with Delta Air Lines’ filing in Form 41, specifically in Table 5.2. Here is what we have.

Delta Air Lines filing

Form 41, Table 5.2 addresses airline financial reports, focusing on expenses. It is detailed and offers good insight into how US airlines are faring in terms of costs. Our interest extends beyond this, as one can delve into the data by aircraft type.

We discovered the misfiling when attempting to understand how American, Delta, and United fared in the twin-aisle segment. Specifically, we wanted to see what the data could tell us about Delta’s move to Airbus twins—was this working out better than American and United’s decision to stay with Boeing?

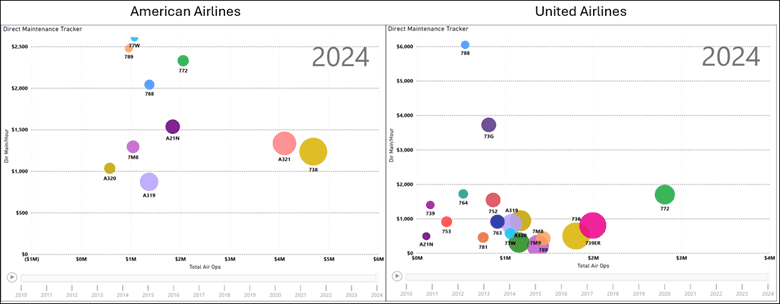

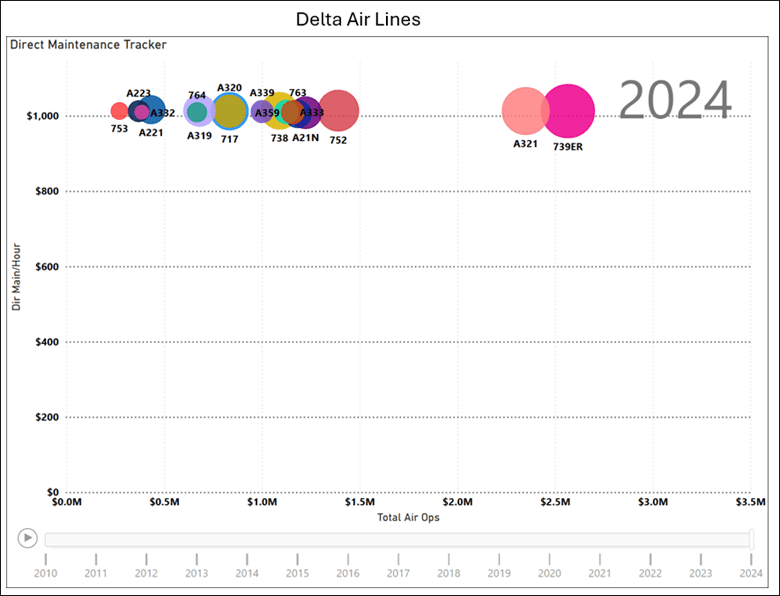

Our analysis found this. The two charts below report the data through 3Q24. The Y-axis lists direct maintenance costs per hour, and the X-axis lists total Air Ops costs.

The charts display the expected results: the busiest models incur the most cost, and larger aircraft cost more per hour. There are interesting items to discuss, such as the 787-8 (788) experience at American compared to United.

However, the Airbus vs. Boeing issue becomes implausible when examining Delta’s results. How can it be that Delta’s fleet all costs the same per hour? The X-axis data looks plausible, while the Y-axis data is clearly incorrect.

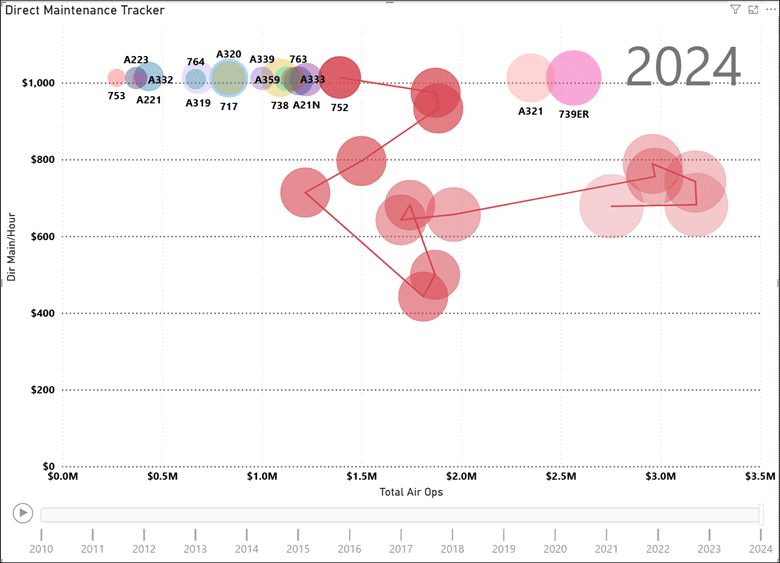

If you are familiar with these charts, you know that clicking the play button at the bottom left creates an animation.

For example, here’s what the animation shows for Delta’s 757-200s.

You would expect that unit maintenance costs rise as this fleet ages, while smaller fleets reduce total air operations costs.

Misfiling Implications

US airlines submit significant operational information to the DOT, a requirement that is taken seriously. The person at the airline who signs off on the filing must be a company officer. Any misfiling carries a legal risk for both the airline and the officer.

The DOT had a fine of $27,500 per day per event for misfiling. Recently, the fine was raised to $34,000. If an airline misfiles and is caught, that cost compounds fast.

If Delta’s misfiling started ten years ago, we estimate that its legal risk of cumulative fines could exceed $111 million. That is serious money.

The US DoT data error

After our presentation to the DOT officials, one noted that the issue was mentioned in 2020. The DOT contacted Delta to refile its information, and the airline complied. It appears no fine was levied and no sanctions issued.

The DOT receives airline filings directly from the airlines. Once checked, the data is processed into an internal database and made publicly available via the Transtats website.

Delta’s corrections were not transferred to Transtats, meaning that Form 41 Table 5.2 data users have used inaccurate information since 2020.

This is a serious issue. Anyone using this data to make a financial or investment decision has been misled, and this error has potential legal implications. At this writing, the erroneous publishing has yet to be corrected.

Risks

There are several risks to consider in this regard.

Airlines Risk

The risk for the airline is obvious—the DOT can levy a fine as described. This happens frequently, but these fines are typically consumer-related. Delta would remain at risk if the DOT had not asked for and received the refiling.

SEC Risk

Most airlines are publicly traded companies subject to SEC scrutiny, and the risk is much more serious here. Taking Delta as an example, a potential $111 million liability to the DOT is a material amount. The SEC could fine Delta for failing to disclose this undeclared liability.

Since Delta did refile, does this absolve the airline from SEC risk? According to a former SEC enforcement attorney, it might not. Delta should have checked to ensure its refiling was published. Delta has every right to find this DOT mishap at least annoying.

DOT Risk

This risk is unusual. The refiling should have ameliorated Delta’s risk. The DOT is responsible for not updating this refiling, which implies that the SEC could sue the DOT. As noted above, Delta might not be entirely off the hook either.

Data User Risk

This risk hits close to home. We are among the data users who download and analyze DOT data, offering opinions and analyses based on our findings.

We assume the DOT has data quality control and audits its data filings.

In our defense, we can point to cases where we found DOT data errors and played a role in correcting the filings. The first was with Alaska Airlines, and the second was with Southwest Airlines. A third case was handled within an industry channel to get Spirit Airlines to refile data.

These errors were evident to us, and we had a path to fix them independently of DOT.

But the Delta misfiling was different. When we first saw this, we emailed Delta PR, and our inquiry was ignored. Unsure of what to do next, we sat on it for a while. When we had previously contacted the DOT about data oddities, we were advised that the data were correct. We had reason to be wary.

These errors were self-evident in the three cases we investigated, and we published stories about them.

We are publishing this account as DOT data users, with our professional reputation at risk. Awareness of the pitfalls associated with using DOT datasets is essential.

For several years, we have discussed Form 41 with industry insiders. The routine response has been that the data is unreliable, and these opinions are frequently stated in impolite language. We now present first-hand evidence of this reliability issue; in this case, the blame does not lie with the airlines.

Big Questions

Some big questions emerge from this saga:

- Why did no other data user emerge before we visited with DOT to inquire about the Delta data error?

- Are there no other users of the public Form 41?

- Can US DOT data users rely on Transtats information?

- The DOT data management process is cumbersome. We were informed about how raw data is imported into Sybase. The system is so old that a significant portion of the IT budget is dedicated to patching it.

- We were informed that the DB1B dataset, which is currently reported quarterly, is moving to a monthly frequency. This dataset is based on a 10% sample of tickets.

- To help understand the magnitude of this switch, consider that the 2025 daily average number of flights through March 20 is 2.24 million. That means ~67 million tickets per month.

- During our visit, it was mentioned that the new dataset will likely consist of a billion records.

- Processing, auditing, and reporting this information will be herculean.

- What can data users do to ensure the quality of DOT data? We learned that the person assigned to Form 41 had been laid off due to the recent government cuts and has now been rehired. Not only technical hiccups but also programmatic hiccups.

Other opinions

We consulted with industry experts to gather their insights on our discovery. These individuals are familiar with industry metrics and reliable sources for their analyses.

William Swelbar is an industry veteran analyst who is familiar with the DOT datasets through his work with the MIT Airline Data Project.

At the urging of many interests in the US airline industry, we created, and updated annually, the MIT Airline Data Project. We created the data project in 2007 – a time when the industry was upside down with bankruptcies, unprecedented oil prices, labor concessions, and fleet-related issues as 1,000 mainline jets were being replaced with regional equipment.

Therefore, Form 5.2 is a critical input into any comparisons or analysis – particularly for fleet, pilot and flight attendant-related data. It is not just the public that relies on Form 41 submissions, but airlines use the data for commercial decisions as well. The MIT Airline Data Project became an important source to many important stakeholders over the years.

The Delta filing referenced was made known to me by the airline that disputed the flight attendant wage and productivity were being used by AFA-CWA in their organizing campaign at Delta and then by AFA-CWA urging us to fix the issue. It was clear that the data was wrong. The MIT project was constantly questioned by those that did not like the accepted calculations we made in preparing the project for public consumption after each update.

Therefore, our hard and fast rule was to only show the data filed, even if experience would know it was wrong. We did not try to fix the data and were urged by both Delta and AFA to address the issue, and we did not. That was not our role.

Any bad filing by an airline that is not fixed will be exposed at some point. This was yet another example of bad data being utilized in a highly charged and emotional union organizing campaign.”

Bob Mann is an industry veteran and first started using US DoT data in the era of paper filing.

“I first saw these errors and omissions about ten years ago in the context of publicly listed cargo carriers’ Form 41 financial data. I advised the client that the published data was unreliable or missing, and sent a message to BTS, who had published the data, without response.

We later spoke several years ago about the Delta Form 41 averaging/aggregation, which whether done purposely or an oversight, once again renders the data useless for comparison purposes.

It’s notable that the agency reached out to Delta to request they refile, which they state the carrier did, the responsible thing to do, albeit ‘caught’, and late, but it is inexplicable that the edited filings were never publicly disclosed.

One presumes the edited filings to be ‘more accurate’, if untimely, but who knows, since they were never published for third-party analytical use.

Public airline financial and traffic data is still very useful for analytical purposes, both internally at airlines and by third-parties, but only if the data is filed, reviewed by the agency, and published timely and accurately, any requested edits or additions to correct earlier errors included.”

Richard Aboulafia is another industry metrics veteran:

“Whether at DoT, the FAA, or the IRS, loss of government oversight resources can cost the taxpayer dearly, and perhaps investors too.“

THE BOTTOM LINE

The old CAB Form 41 data collected from airlines “has been known to be inaccurate by industry insiders for many years,” said AirInsight partner Ernest Arvai, who remains skeptical about US DOT data accuracy. He is familiar with an airline that knowingly changed its cost-allocation ratios to prevent competitive analyses from the era immediately following airline deregulation through the 1990s.

This is not a new problem. What is their value if the industry believes these datasets to be inaccurate and views them skeptically for decision-making? The answer is that incorrect data have no commercial value.

These datasets and collection mechanisms date back to the pre-1978 era of the Civil Aeronautics Board, when fares and routes were regulated, and regulated fares were computed based on reported costs to balance airline profitability and cost control. Post-deregulation, the data requirements continued, even though they were no longer required to analyze and establish fares. The datasets provide comparative data for the industry. Unfortunately, the quality of the data reputation continues to suffer.

Datasets without user trust are of essentially no value. The costs of providing, compiling, storing, and archiving industry data are substantial. The key question is: Would anybody miss the data if it were to disappear?

- If the answer is no, these inaccurate databases should rightfully disappear as an inefficient use of resources.

- If yes, they need to be accurate, with improved analysis and accuracy tests.

Views: 1137