MG 9230

The aviation industry should consider measures to curb non-CO2 (carbon dioxide) emissions from commercial air travel in the next five to eight years. This needs to be done, as their effects are much bigger than have been estimated so far, a recent report from Europe’s EASA says.

The September report was requested by the European Commission and released on November 23. The EC wanted to have an updated analysis of how non-CO2 emissions from aviation affect climate change. So far, the focus has been on CO2. Of the world’s total carbon dioxide emissions, air travel is said to be responsible for two to four percent. This is expected to increase significantly if air travel will double in the next two decades, although this is a pre-Covid forecast. In Europe, CO2 emissions have been addressed through the Emission Trade System directive and from 2021 through ICAO’s Corsia offsetting reduction scheme.

Determining the effects of non-CO2 emissions from the aviation industry has been much harder to quantify. They come from nitrogen oxides (NOx), which are produced during the combustion process in aero engines, soot particles, oxidized sulfur species, and water vapor. Together, these emissions have an effect on the chemical composition of the global atmosphere and cloudiness and contribute to the warming of planet Earth.

“Research has shown that there is high non-linear chemistry of the interaction of NOx with background concentrations of other emissions at cruise altitudes, and the effect of NOx is dependent on the location it is emitted. While the confidence level on the magnitude of the impact of NOx remains low, the current scientific understanding is that NOx still has a net positive climate forcing effect (i.e. warming)”, the report says. The study has been done by leading European scientists and those from the UK and Norway.

Curbing NOx not easy

The problem is not so straightforward, however, as the emissions have a cooling effect in certain circumstances as well which will need further study. The report also adds: “If surface emissions of tropospheric ozone precursors (NOx, CH4, CO, non-methane hydrocarbons) decrease significantly and aviation emissions increase, as envisaged by various scenarios, it is possible that the net aviation NOx Effective Radiative Forcing (ERF) will decrease or even become negative (i.e. cooling) in the future, even with increasing total emissions of aviation NOx. This highlights one of the problems of formulating NOx mitigation policy based on current emissions/conditions.”

Soot is dependent on aromatic content in aviation fuel. “A decrease in soot particle number emissions reduces the number of ice particles formed, increases the mean crystal size, reduces contrail lifetime, and reduces optical depth. This leads to a net reduction in the positive Radiative Forcing (i.e. warming). One study has shown that a 50% reduction of the number of initial ice particles formed on emitted soot resulted in a 20% reduction in Radiative Forcing.”

There is another problem. “Aerosol-cloud interactions, which are separate to contrail cirrus, also have a potentially large non-CO2 impact from changes in high-level cloudiness from soot particle emissions, and changes in low-level clouds from sulfur emissions. Best estimates of these effects cannot be given at present.”

While engine manufacturers have been developing lean combustors for reduced NOx-emissions, the study identifies some side-effects coming from ICAO regulations like “the regulatory approach taken as the ICAO NOx emissions regulations allow for increasing emission index of NOx (g NOx per kg fuel) with engine pressure ratio.”

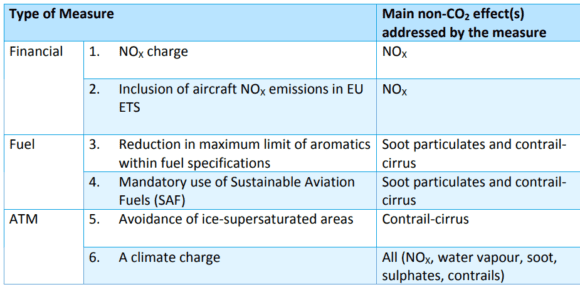

That’s where a number of policy options come into play, EASA says. They are presented as potential solutions to curb non-CO2 emissions in a five to eight-year timespan. The first is the introduction of a NOx charge through taxation of emissions: “This measure is defined as a monetary charge on the total NOX emissions over an entire flight, approximated by certified Landing Take-Off (LTO) NOX emissions data, the distance flown and a factor accounting for the relation between LTO and cruise emissions.” According to the study, there are no legal constraints that prevent the introduction of a tax.

The effect of a nitrogen oxide tax should to “incentivize engine manufacturers to reduce LTO NOX emissions during their engine design process, and airlines to minimize NOX emissions in operation, while taking into account associated trade-offs.”

Another financial option would be to include NOx-emissions within Europe’s Emission Tradings System, identical to the existing scheme for CO2. The effect should be the same: incentivize engine makers to design ‘cleaner’ engines.

What about a climate charge?

The report also considers the introduction of a ‘climate change’: “The concept of this policy measure is to levy a charge on the full climate impact of each individual flight. This makes it both the measure with the broadest coverage and the one that is likely to be the most complicated to implement. The introduction of a charge requires a good estimate of the climate costs at a flight level. Currently, there is no scientific consensus on the methodology to calculate these costs.”

Tackling soot emissions could be done by capping the number of aromatics that are allowed in aviation fuels. The best way to do this is to implement the use of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), preferably by making them mandatory. This requires an EU-wide blending mandate, which has been worked on hard in the past year. Promoting the production and use of SAF’s has been the topic of many aviation webinars and events in 2020, with the outcome of most that the fuel industry needs to really step up if it wants to meet demand.

The study identifies one hurdle to take: “A cost-benefit assessment would be needed to inform a decision on the level of an EU blending mandate. This assessment would need to consider realistic yet ambitious levels, the impact on stakeholders and potential implementation processes (e.g. a dynamic blending mandate that increases over time in order to provide certainty to the market for long-term investments).”

Steer clear of icy clouds

Third but not least, the report sees a role for Europe’s air traffic management (ATM) stakeholders to not only make the much-debated Single European Sky being implemented at last but also use all knowledge to help reduce the build-up of non-CO2 emissions. In particular, ATM could steer aircraft clear of ice-supersaturated areas to prevent the formation of contrails.

“Prior to a flight plan being filed, Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs) and airline operators would need to have all the relevant information (e.g. temperature, humidity) in order to identify the ice-supersaturated areas. The route network would also have to be designed to allow such deviations based on this pre-flight tactical planning.”

With the European Commission and Parliament to debate the EC’s ambitious Green Deal initiative, expect this report to find its way into a hot political atmosphere in the new year or so.

Views: 12