AirbusA350Production

The days of nuts and bolts in aircraft manufacturing are unlikely to disappear completely but the way airliners are built is certainly going to change in the very near future. At least at Airbus, where at last week’s Innovation Days 2019 in Toulouse the media were given an insight into what to expect and how bits and bytes take over from nuts and bolts.

A brief tour around the A350 production line stations 59 (section preparation), 50 (fuselage junction) and 40 (wing junction, cabin installation, and power-on tests) made you realize once again what complex machines aircraft are. Numerous jigs and tools make you wonder however this process will not be man-driven and dictated by robots instead.

Well, maybe not 100 percent, but as Chief Operating Officer Michael Schoellhorn explained, automation is on its way. “Aircraft manufacturing tends to be difficult for automation, people are at the center and will always be. But there is a need to simplify, we need more flow orientation. This business remains people-oriented but we want to automate more if only to respond to an ever older growing workforce”.

In his first 100 days as Airbus COO, Michael Schoellhorn has had a good look at manufacturing procedures. (Richard Schuurman)

Preventing aircraft building from becoming fully automated is the high complexity and the number of highly customized products, combined with a complex supply chain, Schoellhorn observed after his first 100 days at Airbus, having joined the company from Bosch. Yet, with an annual production of 800 to 900 aircraft Airbus needs to make this a mass-produced industry. “We are entering an era of mass-producing of aircraft”, says Alain Tropis, Head of Digital Design, Manufacturing, and Services (DDMS). “If we want to make it happen, we need a breakthrough. We need to be able to ramp up very rapidly, shorten the time a new type gets to the market, and make sure the product is completely mature and on cost”.

Hence the need for digitalization and automation, which on the current production floor is already becoming more and more evident. Workers getting their instructions from tablets, having data presented on ‘smart glasses, wearing exoskeleton suits to assist with tasks in ergonomically trying positions. “What we introduce will always be operator-centered. The blue-collar workers should be able to perform the task”, Schoellhorn says.

More robots

And there will be more robots. Boeing is using robots for in/outside drilling, riveting, and joining fuselage sections on its 777 lines in Seattle for some time and will fully rely on them for the 777X production. Airbus seems to be lagging a bit behind, having introduced two robots for drilling only mid-2018 on the A321 Final Assembly Line 4 in Hamburg. Robots drill 80 percent of 2.800 holes on the outside and upper side of the fuselage sections, join them together, and insert rivets to form a single barrel.

FAL4 is coming to maturity now, said Schoellhorn in his presentation, but Executive Vice-President Programmes and Services, Philippe Mhun, told Airinsight there have been some issues. Apart from deflection of the longer A321 sections and more complex Airbus Cabin Flex-configuration that slowed production, the robots were not as quick: “In FAL4 we decided to allocate a different timing for riveting and joining of fuselage sections of three to four days where the standard process in the other A321 line FAL2 is closer to two days. We will probably not go to two days on FAL4 but can improve in the future. Still, the benefit of automation is that it will reduce workload”.

For this reason alone Airbus will expand automated riveting to other models, but Mhun says the benefits are mostly felt on the single-aisle lines where the rate will go up to 60 per month mid-year and 63 a little later. Schoellhorn added: “FAL4 could be a template for the A220 and other models. Yes, this wisdom will come to Mobile”. (the US production site in Alabama for A320s and from next year A220s – RS)

Prototype of the Smart Drill robot that will be used on the A320 nose section at St. Nazaire from early 2020. (Richard Schuurman)

The next application was shown during the Innovation Days with the ‘Smart Drill’, developed by Airbus employee Jonathan Bioret in five months. Four robots will assist with the drilling of A320 nose sections at the St. Nazaire plant from early next year. “It will not be a fully automated line, but rather assist to human drillers who can take on other tasks. It is rather low-value work that the robots will do”, explained Bioret.

Schoellhorn admits that introducing robots on existing lines is a huge challenge: “It’s easier to do it on a clean-sheet design, but you can still improve when you combine new technologies with old ones. But don’t automate for the sake of automation”.

DDMS

At Airbus, robotization, automation, and digitalization are clustered under the Digital Design, Manufacturing, and Systems (DDMS) method which was introduced four years ago. The key: big data and data analytics. Head of Digital Transformation Marc Fontaine and managing director Euro-North of Dassault Systèmes, John Kitchingman, elaborated on this on Airinsight in February ( http://airinsight.com/airbus-makes-next-step-in-digital-revolution-with-dassault-systemes/ ): “It is about how you use the information once it is digitized through the entire product life-cycle”, Kitchingman said in our earlier story. “The fact is we are constantly re-inventing and recreating information, therefore the ability to use the same information and not have to recreate it into the design, detailed designs, analyses, manufacturing, and production can take massive costs out of the process and make it far more agile”.

At the Innovation Days, Fontaine acknowledged: “Until you have mastered the access to data you have no foundation for this new technology. First, you need to put in place the digital foundations, like the transformation of information management. Secondly, what is missing in most industrial companies is data governance: who is owning the data, who is giving rights to people to access that data, can supplier access it, can we share it with airlines? To put this in place in a company the size of Airbus takes tremendous effort and lots of tooling. We have 200 people who every day are busy releasing and authorizing the data we use and of course cybersecurity is paramount”.

For sharing data on design, manufacturing, and performance, Airbus primarily uses Dassault Systèmes’ 3DEXPERIENCE. Last February, both companies announced an MoU to expand the application during the next five years.

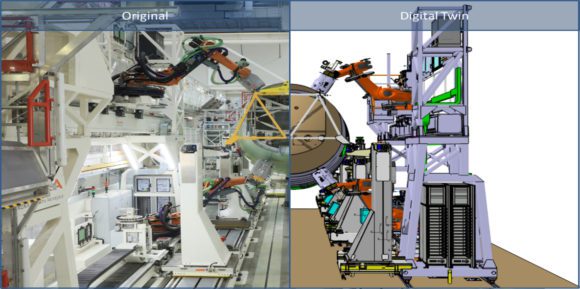

DDMS is also used for making a digital twin of the production process. (Airbus)

Digital backbone

The A350 has been the first Airbus to have been designed entirely in a digital world and this is the way to expand, explains Alain Tropis: “We work first in the single architecture of data in what we call the digital backbone, where we have to make sure that all data is correct. We work with the concept of co-development, which means that we develop not only a virtual model of the aircraft itself but also of the industrial system and services, creating a digital twin. It is important as it helps us to find the best solution for what is needed or best-in-class solution”.

“The next step is the physical execution. When we have done all the studies we have to execute and operate, manufacture the aircraft as it has been defined within the industrial system we have designed. Thanks to the models we have generated we know exactly what we have to master. These data are fed back to the digital twins to reassess in real-time the performance and all that we have simulated and to anticipate the next step”. In other words: use that data for design updates of the next model, but also simulate the effects on a ramp-up and modify production.

Tropis stresses that for a step-up of the digital transformation to be successful, Airbus needs to get virtual modeling and simulation right and to the highest standards. For this, it is using what he called the ‘legacy’ models for cross-checking old and new ways of working.

The DDMS-way of doing things has been used in the design of a new nacelle that should be available in 2022 on P&W-powered A320neo’s. Another application is the digital twin of specific production rigs in which the production system can be simulated, which should improve efficiency and reduce costs. Marc Fontaine said earlier that thanks to DDMS recurring costs of building airliners could be reduced by as much as 25 percent.

The weak link

There is the risk of going this digital road path: will other partners and suppliers be able to keep up or is this becoming the weak link in the chain? “We have to make sure digital transformation is not only a thing within Airbus”, concedes Fontaine. “That’s why we are supporting it on the airline-side and to some suppliers level, but I truly believe that we as Airbus have to play a role within the industrial associations because I don’t believe tier 3 and 4 suppliers will have the means to go it alone. That’s why we need to take some industry-wide initiatives”.

Fontaine thinks the aerospace industry and Airbus, in particular, aren’t doing badly on getting partners and suppliers on board. This is thanks to its open data platform Skywise. Starting in 2017, it has grown from four participating airlines to 70 with over 6000 aircraft providing 4.5 Petabytes of data per month. This is used and shared by Airbus, airlines, and since last year with a growing number of suppliers too who have been benefitting from this to improve their services and products. Not only does this data-sharing help to reduce aircraft-on-ground time by pre-emptive maintenance, in the end, but lessons learned should also result in the next generation of more reliable/easy to maintain airliners.

Materials

While data-driven processes will cause the biggest change in aircraft design and manufacturing, there is another factor as well: materials. The days of pure aluminum and steel aircraft are long gone at Airbus as the use of composites has consistently grown. Of the A350, 70 percent is made of advanced materials. While carbon fiber composites are currently very popular, new materials are on the horizon. Airbus is having a look at using fibers made from the proteins of algae. As Chief Technology Officer Grazia Vittadini explains: “The values of this material are very interesting. There is real potential to go into primary structures. It is stronger than steel and stiffer than certain fibers, but the problem is the supporting resin as at the moment we can’t manufacture it without using carbon”.

Simplifying and reducing parts is another way to improve aircraft design and manufacturing. Many major players within the industry like General Electric, United Technologies, and Liebherr Aerospace are investing massively in 3D printing. Airbus too is looking for applications of additive manufacturing. At the Innovation Days, it showed a printed cabin door hinge. Usually, it is a heavy piece of aluminum with add-ons wielded to it, but the 3D-printed version consists of just two parts and is one-third lighter. Another version combining printed pieces and carbon fiber is even 50 percent lighter.

3D-printed cabin door hinge: weight savings are obvious, but mass production issues are

preventing it from getting on the plane. (Richard Schuurman)

Still, Airbus expressed a somewhat luke-warm attitude to the widespread application of 3D-printed parts in its airliners. “There still is a very viable economic case for 3D-printing if it comes to very complex parts. But if you are talking about standard, serial manufacturing of simple parts, having to cope with rates of 60 to 70 aircraft per month, then the current technology in terms of manufacturing technology for 3D-printed parts doesn’t allow us to cope with that rate”, Vittadini says. Let’s do the sums here: an aircraft with six doors would need 6 x 2 pieces = 12 3D-printed door hinges per aircraft. On the A320-line that’s 720 parts a month. Additive manufacturing currently isn’t up to these numbers, while quality also is not always consistent.

The rough surface of printed parts also makes them not suitable for use in areas of high load, although Airbus and specialists are studying plasma-photo-electric treatment to give the part better fatigue-properties. “3D-printing is definitely suitable for rapid prototyping, for spare parts and parts of a certain complexity. I would wish the manufacturers would be able to cope with our production rates.”

Fast-forward to the 2025 Innovation Days, and expect Airbus to have mastered and implemented all of the technologies described herein its design, manufacturing, and services. Plus new ones, as a new generation of engineers, are being hired that bring fresh ideas to the table. But as Marc Fontaine said: “Deployment of all these new technologies is a huge challenge. It is very difficult to industrialize, very difficult to move it to scale and to all levels.”

Views: 32