Advanced Turboprop

The US airline industry faces a hurdle found nowhere else, a Scope Clause that limits regional airlines to protect pilots at the Big Three Network airlines, American, Delta, and United. While this limit is seen as a sort of tyranny among airline managers, its creation by the pilot unions was a direct outcome of the commercial abuse pilots at these airlines suffered through time after time.

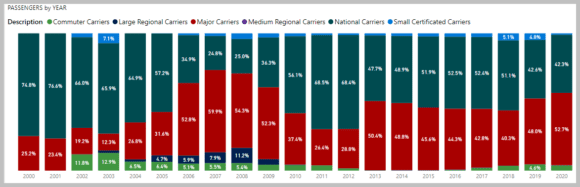

In the US it helps to understand the impact of the airlines outside of the Big Three. The following chart lists the number of passengers transported in the US domestic market in market share terms.

Based on this chart a reader might think that the major airlines are all we should be concerned with. But the following chart provides another perspective. This chart lists the share of flights and we can see the smaller airlines play a far greater role in the market than is commonly thought.

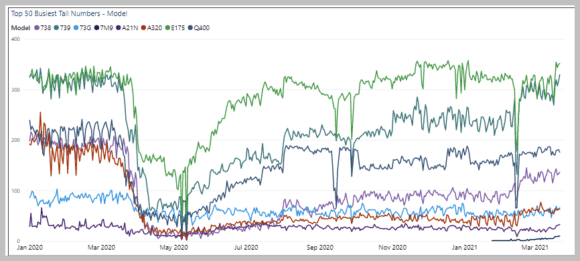

The market behavior has been deeply impacted by the pandemic. As the majors and national carriers saw sharp drop-offs in traffic they had to search for a way to move the smaller traffic volume at far lower costs. This was accomplished by deploying the capacity at regional airlines. To get a granular look at how the US airlines reacted to the pandemic, the following chart lists the number of daily flights by regional and single-aisle aircraft. The size of the gap between these fleets seen in the first quarter of 2020 has shrunk considerably.

To take the example one layer deeper, here’s what the Alsaka Airlines fleet has been doing. Notice their E-175 fleet is busiest and the Dash8 fleet is the third busiest. In the US, Alaska is unique among the big airlines in having a fleet of turboprops it is able to deploy. That flexibility has proven very useful during the pandemic.

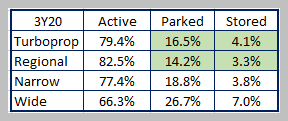

The US airline industry parked large numbers of aircraft. Globally, by the third quarter of 2020, the ratio of active parked and stored aircraft is shown in the following table. Notice that turboprops and regional jets remained busier than the single-aisle or widebodies.

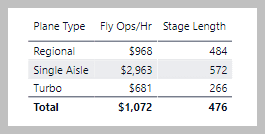

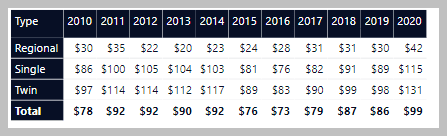

The industry went from a pilot shortage in February 2020 to a pilot surplus 30 days later. The airline industry went into a frantic strategy to preserve cash. Planes were parked, crews and employees laid off. Ticket refunds were held on to. The need to save money was clear as this next table illustrates. Here we list the Air Ops cost per minute. Running an airline is very expensive. When one considers the number of flights and fleet sizes, these numbers spiral to very large numbers quickly.

The need to drop trip costs is self-evident. Low seat cost is only useful when you can fill the seats. During the pandemic, the airlines could charge relatively high fares, but they need low trip costs and ensure they fill smaller aircraft to remain profitable. Initially, traffic dropped off to about a third of the pre-pandemic flow. Airlines could not unwind their cost structure fast enough and the impact on their cash burn was devastating. The following table provides a sense of just how cash burn was impacted. This table lists the flight operations per minute by aircraft type.

From the chart, it is clear why widebodies were sent off to the desert if they were not being used as converted freighters carrying PPE. Most of the older single aisles went to the same parking lots. But the regional aircraft offered some possibility of keeping load factors high and moving the smaller loads at better costs.

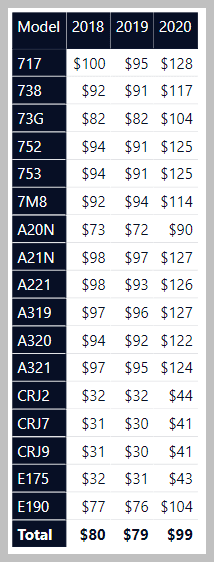

The following table lists US-operated regional and single-aisle aircraft flight operations cost per minute. Older aircraft cost more, and therefore many were parked during the pandemic. Many of these older aircraft are likely to stay that way.

We have not broken down these costs on a per-seat basis as that would be too detailed. What we want to highlight here is the low costs offered by regional jets.

As we showed in the load factor chart above, regional jets offered the best load factor and cost combination. However, deploying these came with a limit – Scope Clause.

The initial shock of the pandemic provided the industry with some breathing from labor unions. Many senior pilots chose early retirement packages. This opened pilot seniority lists, allowing younger pilots to move up.

But in speaking with some senior pilots with five years or more to go until retirement, they refused early retirement options and kept their jobs. As one pilot explained, these last years are the best paying and offered the best route selection. This pilot wasn’t going to give that up. Which meant at his airline a junior pilot was furloughed instead, so he could stay.

If we see that regional jets offer US airlines compelling economics, why deploy more of them? The answer is twofold, first, only one model is being offered as a new delivery, the Embraer E-175. The formerly Bombardier CRJ series now maintained as MHIRJ just made its final new delivery. Second, these aircraft fall within the Scope Clause. This means the airlines using them for feeder services are limited to the number they can deploy.

The following table lists the operational costs and average stage length of the US airline industry for three aircraft types.

Note the attractive turboprop economics compared to the other regional aircraft listed. ATR’s turboprops are in service in the US market as freighters and there are seven ATRs flying for Hawaiian (operated by Ohana and Empire). Silver Air has also been operating ATR aircraft since 2019 and will soon be operating nine -600 series aircraft. We do not have detail on ATR ops. The Q400 (Dash8) data comes from the sizable fleets at Horizon and Alaska.

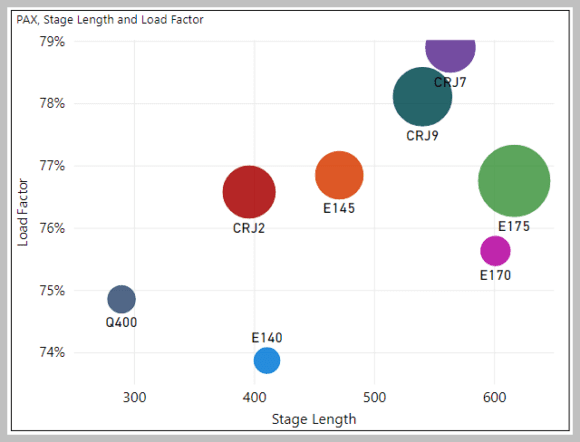

Turboprops from both ATR and De Havilland Canada offer pretty much what regional jets do: three classes of service-capable cabins, high speeds, and comparable range. To illustrate how the Dash8 (DoT still lists them as Q400) turboprops compete in the US market, look at the following chart. We are once again using 2019 data. The ball size is driven by the number of passengers.

The oldest regional jets in US service most in need of replacement are the 50-seaters: the CRJ200, E140, and E145. Prior to the pandemic, US airlines had started replacing these with 76-seat CRJ900 and E-175 as well as re-purposed CRJ700 in the form of the CRJ550.

Given that the CRJs are no longer produced, and E-175 supply will be limited, it seems appropriate that large turboprops should be reconsidered for US regional service. In terms of the Dash8-400, it has speeds that compete favorably with RJs because it does not use the same altitudes as the regional jets – saving substantial time by not climbing and descending as much. And the fuel savings of a turboprop means that its carbon footprint lower than the RJs. A factor that is becoming increasingly important for the sustainability of air travel.

The highest ranges are easily within the capabilities of the Dash8 and ATR. OAG analysis shows 79% of flights operated by regional jets are below 500NM, which is within the usual range flown by turboprops globally. Also, because of the crowded airspace in the US, jets regularly begin their descent and deceleration earlier than the optimal flight path they might want to follow. Sticking with Dash8, its cabin can be used for 65 seats and thereby offer three classes of service. Its cabin can be configured to allow for ample carry-on bags – which is not the case on the many regional jets. It also has a large cargo bay for transit bags.

ATR is the only in-production turboprops with a glass cockpit and state-of-the-art avionics. The ATR -600 cockpit has all the PBN capabilities that modern jets have (Baro-VNAV, LPV, RNP-AR) for smooth and optimized operations. The turboprop can seat up to 70 passengers on a dual-class layout. It offers a spacious cabin with 18-inch-wide seats and capacity for large carry-on baggage in overhead compartments in a ratio per passenger comparable to a single aisle. It is also possible to install standalone WIFI entertainment systems. It is a Modern aircraft with an elegant and comfortable cabin offering an improved travel experience to passengers when comparing with old, noisy regional jets.

Sustainability is also an important aspect; ATR aircraft burn up to 40% less fuel and emit up to 40% less CO2 than a similarly sized regional jet. Importantly, in terms of contributing to a more responsible aviation industry, the ATR boasts 50% Sustainable Alternative Fuel (SAF) capability. In terms of being a good neighbor, ATR aircraft are also fully compliant with the standards in ICAO Chapter 14. In fact, ATR aircraft emit two times less noise during take-off and landing than regional jets.

Since the US airline industry will remain under severe financial pressure for some time, the case for a revisit to the turboprop seems apropos. Offering what regional jets offer by way of cabin capacity and performance but at about 25% lower costs, what’s not to like? Moreover, rather than see several smaller communities lose air service because of regional jets costs, turboprops deliver both community connectivity needs at reasonable economics, which is to say more profitably than regional jets.

Views: 29

Really nice article with relevant data and a good flow. Thanks. Brought me up to speed on information I needed.