Airbus and Boeing represent the largest sectors of commercial aerospace with their single aisle aircraft. As both companies transition from their current generation to next generation, what patterns can we discern?

For example, both OEMs talk about up-sizing – particularly when they describe the under 150 seat market. They offer their orders as evidence that the world is moving up. But even as they say this, the orders Bombardier and Embraer have started to build in the sub-130 market exceeds what Airbus and Boeing have. So the big duopoly argument holds, but only sort of.

Beyond the 150 seat market it starts to become messier. Airbus’ A320 at 150 seats seems to be a standard that airlines like. Boeing’s 737-800 at 162 seats competes with the A320, but has 12 more seats. Boeing has to discount those seats to match deal Airbus offers. The annoyance and cost is the reason we see the MAX7 now has grown to match the A320, allowing Boeing to recoup its costs on the larger model. However, one should note that the MAX8 is 2.2m longer than the A320neo. These extra 12 seats come at no extra trip fuel/costs – the MAX8 offers considerable revenue upside. Moreover, Boeing claims the MAX8 offers more air time (9 hours) than the A320neo (8 hours), and also offers longer periods between heavy checks and higher dispatch rates.

Then at the high end, we compare the 737-900 and A321. The generally accepted wisdom is that Airbus is outselling Boeing because the -900 and MAX9 do not offer airlines what they need – specifically more range and capacity.

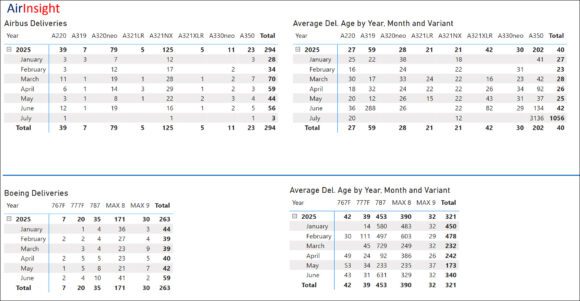

What does the data say?

First Airbus. As we see the A320 has moved from a historical 59% to 72% on the NEO. The A319 has moved from 21% to 1% on NEO. The A321 has moved from 19% to 27% on the NEO.

Airbus has lost momentum on the A319. There are 1,430 A319s Airbus wants to keep on-side and no doubt could say has largely moved up to the A320neo. But the total numbers are short, so we think the A319 has lost traction. But the A320 is looking good; current A320neo orders looking like 86% replacement. That serves to underscore the popularity of the A320 – an aircraft that Airbus got absolutely right. In terms of the A321, we see a move from 19% to 27%. Clearly there is strong interest in the A321 because it offers the range/payload mix airlines want. The A321 offers airlines trade-off choices – up to 220 seats or up to 4,000NM range. If the market is indeed fragmenting, then aircraft that handle long thin routes offer a specific solution. The A321 meets this requirement well because there is a neo and an LR version to choose from.

Now let’s look at Boeing. There are some developments that make comparison subtler. In the NG range, the -700 was the base model. On the MAX it’s the MAX8. Boeing has moved its center of gravity – no doubt because the -800 has been such a success.

The -700 is 19% of the NG fleet and we estimate is 3% of the MAX orders. Like at Airbus, there has been a swing away from the smaller models, leaving opportunities to Bombardier and Embraer. Like Airbus, Boeing added seats to escape the competition below 130 seats. Note the revised MAX7 is focused on squeezing the A320neo (MAX7 below and MAX8 above) and outclassing the A319neo. The -800 is at 73% of the NG fleet and we estimate 78% of MAX orders. There has been growth, no doubt by some customers up-sizing. But there is also the “deposit game” – customers put down a deposit on the MAX8 and then switch to the MAX9 when the aircraft starts being built. This saves on deposit costs. Even so, we see the -900 is at 8% of the NG fleet and we estimate 19% of MAX orders. So, in fact, Boeing has seen a strong move towards the MAX9 from the -900. This is growth for the top end, just like at Airbus. And as mentioned, that may even be low since the deposit game is in play.

Boeing’s MAX orders are some way (32%) behind the level of Airbus’ neo orders. The table below shows how the numbers are moving. Since Boeing does not report MAX order breakdowns, the numbers shown are our estimates of order breakdown.

Even though Boeing is behind in next generation orders, the company is confident it can catch up. After all, it has more -800s in service than Airbus has A320s in service. The chances of customers switching OEMs is low and the -800s will mostly likely convert to MAX8s.

Even though Boeing is behind in next generation orders, the company is confident it can catch up. After all, it has more -800s in service than Airbus has A320s in service. The chances of customers switching OEMs is low and the -800s will mostly likely convert to MAX8s.

The takeaway here is that both Airbus and Boeing are struggling at the low end. Both companies are trying to squeeze more out from their smaller models. Boeing has up-sized its MAX7 to reach 150 seats in LCC configuration. Airbus has gone to 140 seats for their equivalent seating. In the middle of the market, Boeing has yet to see the same level of uptake as Airbus on its next generation. At the top end, Airbus has seen more than replacement level already. Boeing has also seen this, supporting the contention that airlines are indeed up-sizing. But Airbus is outselling Boeing in this segment by a factor of 2.1. Boeing is confident it will catch up and can point to the fact that the MAX9 orders are 28% more than the in-service -900s. Boeing’s talk of a MAX10 suggests they realize their MAX9 needs more support to catch the A321.

Airbus and Boeing are so busy facing off with each other from 150 seats and up, they don’t have time to look below that anymore. Bombardier and Embraer have a vacated market they move into and only worry about each other. Based on the ceo and NG fleets, and even allowing for 25% up sizing, should leave a market of nearly 2,000 aircraft to the new entrants. Easily enough for both to achieve breakeven on their new aircraft.

Views: 8

Addison

All these facts, all these purchases reflect a single economic vision: a stable environment and economic projections of increased air traffic and congested airports. So there are hypotheses to identify. It is working with other assumptions to change possibly the portrait. For example, it was announced that terrorist acts will become permanent. We know there will be impacts on tourism. If Putin continues to surprise us with his aggressiveness, again the capacity of airlines likely to be affected. And now the possibility of war between Pakistan and India? We are moving towards an uncertain world, fragile and it has nothing to do with the timing of purchases of aircraft. Finally, can we also anticipate a cycle end of the “sardine class,” 4000mn, 220 seats in the single-aisle, really? In short, it is for when an article more focused on forecasting with different scenarios?

How did AirInsight come to figure of 6000 aircraft in 2010 to a figure of 2000 aircraft in 2016 for new entrants? What happened to the other 4000 units? Do I need to mention that the discrepancy is huge? I would appreciate if AI could offer an explanation for these numbers, which are clearly at odds with each other. It’s actually embarrassing.

No doubt both B737 & A320 are great planes, but no doubt also is there that Airbus has dominated the single aisle type all over the world. Airbus technology proves to be more advanced and better to be used for future. Airbus cleverly play the game with A320 before and recently with 321 planes and understanding the market requirement.

I doubt Boeing will be able to coupe with Airbus single aisle products and client satisfaction at least for the coming short time (10 yrs.)