b8bb2ecded34736d622936a647d12723bcb7a075 jpeg 7cb45d5c14101c4eeaf5aeff33511ab6a9238e70

Karma is the sum of a person’s actions in this and previous states of existence, viewed as deciding their fate in future existences. For this story, it isn’t a person so much as a corporation and most definitely in its current state of existence.

The corporation is Boeing Commercial Airplanes and the outcome of the karma is where that company sits now.

The story starts with the incredible moment in 2011 when American Airlines nearly opted exclusively for the Airbus A320neo but gave Boeing a second chance and which begat the MAX. Looking back, that moment may be one of the industry’s “great moments” when a seismic shift happened and was hardly felt.

Boeing was clearly caught off guard. They were not expecting this, and the MAX turned out to be the product of something like a shotgun marriage. Conceived in haste and developed with all kinds of constraints, but especially time, as it was a response to the A320neo.

Airbus had a clearer horizon as it wasn’t responding to a competitor. Boeing turned inward and was consumed with the MAX, the 787, and the 747-8. There was too much going on to look up and see how the world was changing. Not so in Toulouse, where John Leahy famously observed that Airbus would not make the same mistake as Boeing (“We will not do with Bombardier what Boeing did with Airbus,”), which had ignored an emerging Airbus – they were not going to ignore what was going on in Montreal. It was there that Bombardier was cooking up a high risk, but a very impressive project called the C Series.

Bombardier struggled through, with the C Series eating every dollar and labor hour it could grab. A former Bombardier executive noted at that time if you were working on the C Series, the checkbook was open. The outcome was an airplane that was far better than Airbus or Boeing would have reason to expect. The regional jet maker pulled off a technical coup. It had the technical expertise to show the aviation world what a new small jet could be. But the birth pangs were severe, and Bombardier was crippled by the project. Its turboprop and regional jet business were resource-starved, giving Embraer and ATR opportunities they didn’t miss. Airbus, ATR, and Embraer moved in on Bombardier’s weakness. Boeing seemingly continued to ignore Bombardier, but in fairness, they were distracted.

Boeing seemed to wake up to the threat of the C Series when United Airlines very nearly selected it. Boeing, to prevent that deal, did the classic Boeing thing – they repriced their 737. United selected the 737-700 over the C Series. But, the temerity of Bombardier! This uppity behavior had to be checked. Then shortly after this, Delta went for the C Series in a big way – ordering up to 125 aircraft. Then matters spiraled quickly.

Boeing accused Bombardier of dumping and filed a complaint with the US government. Bombardier was slapped with huge dumping duties. Internally at Bombardier, there was panic. The company was weak, and this was a body blow. The warming market for the C Series instantly went into a deep freeze. Boeing crippled C Series sales campaigns and pushed Bombardier, which was “all in” on the C series, to the brink.

Karma is a real thing – part one

This reaction by Boeing was a clumsy step – brutal, and crucially, seen as brutal. Bombardier appealed against the government’s duties. The ITC hearing was a display of Boeing power – its lead attorney owned the room. But brutal isn’t appealing. The one party in the hearing that didn’t blink was Delta Air Lines. It was when the airline calmly explained to the ITC panel why it selected the C Series and demonstrated that Boeing did not offer what it was looking for, that the entire circus turned. Delta Air Lines CEO Ed Bastian said “we do not expect to pay any tariffs and we do expect to take the planes“, maybe with a delay, but he had “various other plans and alternatives“. Delta was not alone, other US airlines were also supportive of Bombardier.

Even so, when the panel’s decision came back 100% against Boeing, it sent a shock wave across the industry. It was a pyrrhic victory for Bombardier. The company was in deep financial trouble. The cost of program delays and market conditions had stretched its resources. The hearing pushed them over the edge. There was no margin. To save Bombardier, programs were going to be sold and the crown jewel C Series would go first.

Boeing’s luck changed the day the panel’s findings were announced. Its karma was now present. Matters started to fray as sentiment (also here) went against Boeing. Boeing moved to do a deal with Embraer after Airbus made the commercial aviation deal of all time acquiring the C Series program. Once again Boeing was flat-footed by Airbus. Airbus paid Bombardier under $600m while Boeing’s deal with Embraer was going to cost over $5Bn. (Side note: If Boeing had bought the C Series, how different things would look for that company today)

But karma wasn’t done – part two

The Boeing deal with Embraer fell through because Boeing claimed the Brazilians weren’t delivering on their side. No details have emerged yet as the breakup is being challenged in court. Boeing will probably settle out of court as any information coming out may look bad for Boeing. The Brazilians literally tore Embraer’s commercial heart out of the structure to make the deal work. They claim it cost them $100m. and that number sounds plausible.

But karma still wasn’t done – part three

Then came two MAX crashes with nearly 350 fatalities. The MAX was grounded for 20 months and Boeing was dealt a severe blow to its reputation. The blow was severe enough that even the FAA came under a cloud as the party responsible for certifying the MAX as safe. Congressional hearings added more pain, as the process of bringing the MAX to market identified several questionable decisions. Boeing paid and paid. (Another example, the apparent 70% discount IAG got on its 2019 MAX order at the Paris show)

Boeing’s pristine reputation for quality engineering was sullied. Its corner-cutting on the MAX looked bad. As this was coming out, the 787 started having assembly quality problems. Which the program didn’t need after its rocky start. Then came the KC-46 quality problems and a very unhappy critical customer, the quite vocal US Air Force.

The MAX is now flying and so far, so good. But Boeing isn’t done paying yet. Some MAX customers have gone out of business because the service return came during the worst air travel crisis ever. Consequently, there are several “White Tails” looking for new homes. Those customers still taking their MAXs do so with additional “price adjustments”.

Karma part four – the setup

Here we are, early in 2021, and are we about to watch another blow land on Boeing? At this writing Boeing’s biggest customer Southwest Airlines is taking delivery of its MAX8s. But Southwest has another item to work through – it’s aging 737-700s. Nearly a third (29%) of these were not originally delivered to the airline, being bought second hand. These -700s are worked hard. Southwest gets an average of 12 hours per day out of a -700, compared to 11 at Alaska, nine at Delta, and seven at United. Nobody works a -700 as hard as Southwest.

Although fuel is cheap now, Southwest wants to drive seat production costs down. The market is changing, and a new threat is on the horizon, David Neeleman’s Breeze. Starting with second-hand E-190s, this airline also has 60 A220-300s to come. Mr. Neeleman is the world’s most successful airline entrepreneur. Anything he does is a manifest threat to the consolidated US airline industry – and Southwest appears to be squarely in his sights.

Southwest is currently evaluating the A220-300 against the MAX7. This is a diabolical outcome for Boeing. The A220 used to be called the C Series. The very thing Boeing complained about to the US government has come about; the A220 is a manifest threat to the 737 MAX7. Boeing’s then vice-chairman Ray Conner told the ITC: “It will only take one or two lost sales involving US customers before commercial viability of the MAX7, and therefore the US industry’s very future, becomes very doubtful.” Turns out he may have been right. But this was Boeing’s own doing, losing Delta and Southwest is not the fault of the customer. Airlines define what they need for each mission, not the OEMs. Boeing is not cleverer than its customers.

Because of Boeing’s attack on the C Series, Airbus ameliorated Boeing’s complaints. There is an A220 FAL in Mobile, Alabama. The once Canadian C Series is now an American A220. Delta has taken several deliveries from there already.

Moreover, the clever ideas Bombardier put into the C Series have proven to deliver as promised, even if it took Airbus to unlock the value. The aircraft’s economics are better than expected. It is now such a popular aircraft that Airbus has a growing waiting list. The pandemic served to make the A220 more popular.

Now, to make things worse, Boeing’s most influential 737-customer is seriously eyeing the A220 as an alternative to the MAX7. The MAX7 was seen as a “shoo-in” at Southwest, an airline built on the 737. Boeing even made the MAX7 slightly bigger than the -700, seating 150 for Southwest. Southwest has a token order of 30 MAX7. These orders, in our view, are likely to be converted into MAX8s. Boeing cannot contractually hold MAX customers to their original orders because the 20-month grounding moved all the bargaining power to customers, whose contracts are voided by the delay.

The MAX debacle damaged airline and lessor relationships with Boeing. The level of trust between Boeing and its customers is much reduced as shenanigans from the MAX development emerged. The fact that decision-makers at Southwest are even considering an alternative to the 737 signals that even at Southwest, there is a realization that they will inevitably move away from the 737. Let that sink in for a moment. A tectonic shift is underway.

Karma part five – the outcome?

Here’s how the next act of karma could play out. Southwest, like all big airlines, undertakes extensive research into fleet decisions. (Southwest was an early target for Bombardier and their C Series) As of January 2021, Southwest had 477 737-700s in service but only has 30 MAX7s on order. By comparison, Southwest ordered 280 MAX8s and has taken delivery of 47 already. This highlights their paltry interest in the MAX7. Whereas 65% of the airline’s fleet is based on the -700, only 10% of MAX orders are focused on its replacement. Southwest is likely looking for about 500 aircraft in the 140-150 seat category.

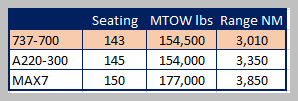

What do we know about an A220-300 vs MAX7 competition? The table lays out some key data points.

The 737-700 is shown as the benchmark. At first glance, it seems the MAX7 offers more. The crucial number here is the MTOW. The A220 weighs in at 1,062 pounds per seat. The MAX7 comes in at 1,180 pounds per seat. Since these aircraft fly shorter routes, the lighter aircraft beats the heavier, limiting the extra range advantage.

Will Southwest use 150 seats, or stay closer to its current 143 on the -700? (At 149 seats the operator needs three flight attendants, making 150 seats unlikely) If they use 145 the weight per seat on the MAX7 goes up to 1,220 pounds per seat, making the A220 15% lighter per seat.

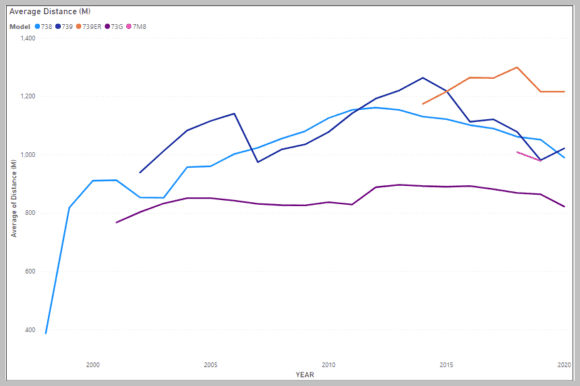

Aircraft weight is the MAX7s Achilles heel. Whereas the MAX8 is right in the sweet spot, the MAX7 gets tripped up as you can’t lose enough weight with a shrink. Estimates are that the A220-300 could deliver a 7% better fuel burn than the MAX7, all things being equal. And as ranges get shorter, the light airplane does even better. Moreover, look at the average ranges actually flown by 737 in the US. The US-based 737-700 fleet typically flies under 900-mile segments. The range of the A220-300 and even E195-E2 should be more than sufficient. Southwest can serve Hawaii with its MAX8s, allowing the A220 to handle corner-to-corner markets within the mainland.

In terms of 2019 flight ops, at Southwest, the 737-700 had 52.2% of its operational costs in fuel burn, and for the 737-800 was 54%. Shorter flights mean higher fuel burn, in total 2019 ops cost per hour, the 737-700 cost $3,315 and the 737-800 was $3,274.

We don’t have A220-300 data yet, but 2019 A220-100 ops costs per hour were $3,030. The A220-300 could end up below $3,000 per hour. Southwest puts an average of 12 hours per day on their -700s. If, for example, the A220-300 comes in at $315 less per hour than the -700, the aircraft could save the airline nearly $4,000 per day per aircraft. That is a significant number, and annual savings could be many millions of dollars. Multiply the savings over 500 aircraft to get an idea.

What is the MAX7 expected to cost? The MAX data is, understandably, thin. The 2019 key number for the MAX8 at Southwest was $3,675 ops cost per hour. (The 2018 number was $3,185 per hour and the 2017 number was $3,005) If we use the same proportions as the difference between the -700 and -800, we estimate the MAX7 might run at around $3,045 per hour, using the lowest MAX8 number. If the A220-300 can get to $3,000 per hour (which is not a reach based on the A220-100 numbers), then daily savings for Southwest would be around $540 per aircraft per day. A fleet of 500 A220-300s could potentially save $270,000 per day over the MAX7 while moving the same payloads.

Southwest’s fleet deployment tells the story – the 65% of the fleet (-700s) undertakes 72% of daily flights. This means the costs incurred by this fleet becomes a key issue as Southwest drives its costs down, and even small savings add up quickly. When we look at arrival delays by aircraft type for Southwest, in 2019, 73% of the late arrivals were 737-700s. Once again, out of proportion to its fleet size, because they do more turns per day. For 2019 we estimate Southwest’s operational costs per minute at $75 and typically delayed arrival cost of $751. According to the DoT definition of late, 15 minutes delayed, 17.1% of Southwest’s 2019 flights met that DoT definition.

Not to belabor the point, Boeing has a steep hill to climb. The MAX7 isn’t particularly competitive with the A220-300 (or even the E195-E2 for that matter). United knew this but bought Boeing anyway because of pricing. Boeing’s pricing power is prodigious. But that was then. Now airlines face a different world. A world where loads are lighter, remain below breakeven and look to stay that way for some time, perhaps until 2023. Southwest may have built its business on the 737 but remaining loyal to the 737 can’t be assumed. It seems that Southwest’s decision-makers are coming around to a future that may not be 737-centric.

Could this become a regular future sight over Dallas?

What are the reasons for Southwest to stay with Boeing?

- Pilots are trained for the 737.

This is a real argument, but once your sub-fleet reaches a certain size it no longer is a hurdle. Nico Buchholz explained to us that 50 was his watershed number when he was at Lufthansa. So, if Southwest considers up to 500 A220s, clearly pilot training isn’t going to be an insurmountable hurdle. Indeed, if the airline goes for 500 A220s, it will become Airbus biased.

- Boeing will be cheaper.

This is a two-edged sword. Can Boeing afford to sell 500 MAX7s at the kind of prices Southwest requires? In a word, No. The MAX program is way over budget and a replacement for the 737 is already being planned on computer screens. Boeing is also not aggressive in marketing the MAX7 – we know of a recent deal where the MAX8 was offered at $40m and the MAX7 was offered at $36m. The customer bought the MAX8 – no surprise. Moreover, while Boeing has a clear floor price it can’t go below, we think Airbus has, potentially, a lower limit. Airbus has a low R&D budget now and therefore more pricing flexibility. Airbus can, possibly, price the A220-300 low enough to where Boeing can’t match. What does this mean? Boeing cannot go too low because doing so takes away the financial requirements to help fund the 737 replacement. Airbus can bleed Boeing through aggressive pricing. Besides, if Boeing (and CFM) were to offer a “screaming deal” it is highly unlikely to be for 500 MAX7s. Neither party would find that attractive – another Airbus advantage.

What are the reasons to switch to Airbus?

- The A220-300 is the better airplane.

Yes, it is, and it has better economics and is decades newer. It has sufficient range for Southwest to serve US West Coast to Hawaii, or Miami to Seattle and Boston-San Diego. What more does the MAX7 offer that Southwest would find irresistible?

- Airbus A220 production is too low.

The primary problem ordering the A220 is supply; there is more demand than supply. Would Airbus double the size of the Mobile FAL for a Southwest deal? Considering this line will churn out 500 identical A220-300s, you bet. This volume will drive down the A220’s costs which is what Airbus has been telling its supply chain since it took over the program. Also, this body blow to Boeing is worth being chased by Airbus as it provides them with other advantages. For example, a stronger A220 program allows for the offering of the long-rumored A220-500 that Air France wants to replace its A320ceos. An A220-500 also likely thumps MAX8 economics, too. So there are good reasons for Airbus to chase this deal.

Karma part six – the closing act?

If, and it is a big if, Southwest switches to Airbus to replace its 737-700s the downstream implications are very big.

- Airbus

This would be among the most significant fleet switches ever. Airbus would move into a nearly unassailable market share advantage for single-aisle aircraft. The industry supply chain would recalibrate away from Boeing. - Boeing

The body blow would be catastrophic. Could it be fatal? Boeing’s bread and butter program is the 737. The MAX crisis has shown how dependent Boeing is on that model. If Southwest were to switch, the influence alone would be tremendous. The MAX family would fray at its edges. At the lower end, the MAX7 would be done for. Already the MAX9 and MAX10 are weaker than their Airbus competitors. No matter what Southwest does, Boeing can’t win. Boeing can’t afford to subsidize a 500 MAX7 order (How much help would GE and SAFRAN help?) and they also can’t afford to lose Southwest. It’s an awful conundrum.

- Embraer

Yes, Embraer gets a mention! ! Boeing needs an optimized smaller aircraft and Embraer could be an option that is less damaging to the Boeing-Southwest relationship than the introduction of an Airbus. The E2 fits the capacity and is even lighter and, arguably, more optimized than A220. It has a shorter range but normally longer flights are flown by larger aircraft because of the lower yields. A fleet composition of MAX8 + E2 could be the most optimized fleet for Southwest. Airlines needing to “right-size” and come out of the pandemic with smaller aircraft would default to the Embraer E2 family. These are fine and very effective aircraft, and highly competitive with the A220, lacking only in being supported by a giant like Airbus. Indeed if Southwest were to consider a non-Boeing option, the E2 warrants a look. If Southwest were to still select the A220, Embraer also wins because Southwest will have endorsed the new aircraft in this segment. Airbus realized the advantages and bought the C Series even though it has the A319neo. Having an aircraft in this segment was an advantage Boeing was supposed to have with the E2 family.

It’s amazing to think that the very firms and programs Boeing brutalized may come out shining if Southwest Airlines makes a switch to the C Series, er, A220.

Delta Air Lines explained to the ITC that Boeing didn’t offer what they needed, regardless of what Boeing said about Bombardier dumping the C Series. Now, by the looks of things, Southwest Airlines will be telling Boeing it doesn’t offer what is needed. Ignoring Delta on the 737 is one thing, but ignoring Southwest? Not listening to these industry-leading customers may turn out to be one of Boeing’s biggest mistakes. Ray Conner’s nightmare may be coming true and Boeing cannot blame Bombardier. Watch Boeing’s short interest to see the process play out.

We wrote earlier that this is the industry’s biggest story this year and we remain of that view. Karma is real.

Views: 17