2024 12 16 08 11 19

As year-end approaches, OEMs are struggling to meet announced delivery targets. Supply chain constraints drive this year’s struggle, a vestige of the pandemic’s impact that continues even years later. During the pandemic, OEMs, airlines, and the supply chain overreacted, causing a level of panic never seen before in anyone’s living memory.

American Airlines retired its 757, 767, and A330 fleets. Turns out that was an overreaction. United converted its 777s into “preighters” to keep its crews and aircraft busy – that was a good decision in retrospect. All airlines laid off too many senior pilots. Hindsight is 20-20 vision, as they say. Every company had to make choices based on circumstances – some would bet better than others.

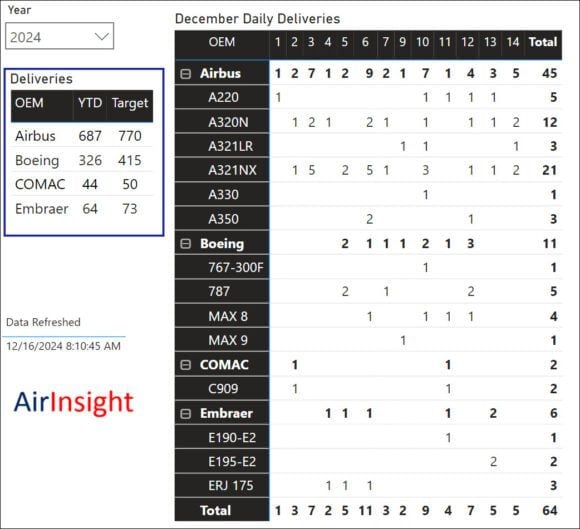

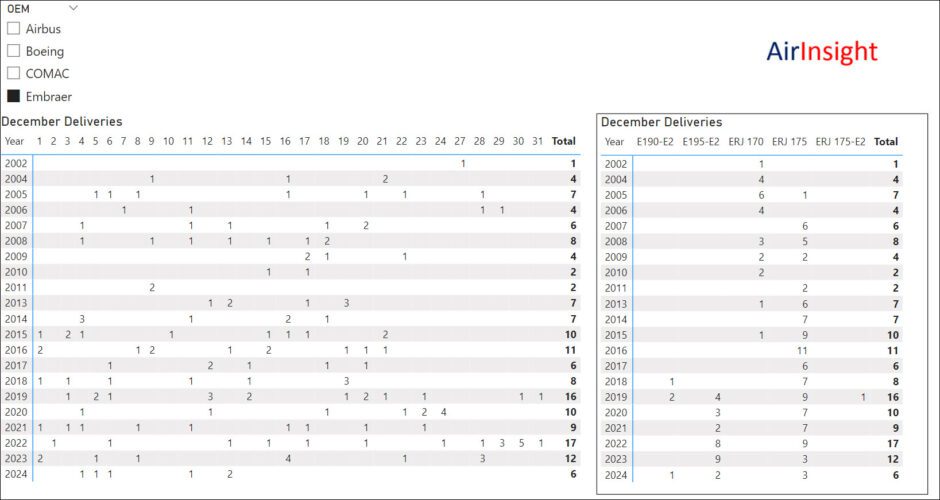

Against this backdrop, one must examine December’s delivery rates. Over the past week, our social media followers have seen the following chart. This model, which is updated daily, provides a more detailed view of deliveries. Our delivery tracker focuses on current production models.

Let’s look at each of the OEMs for perspective.

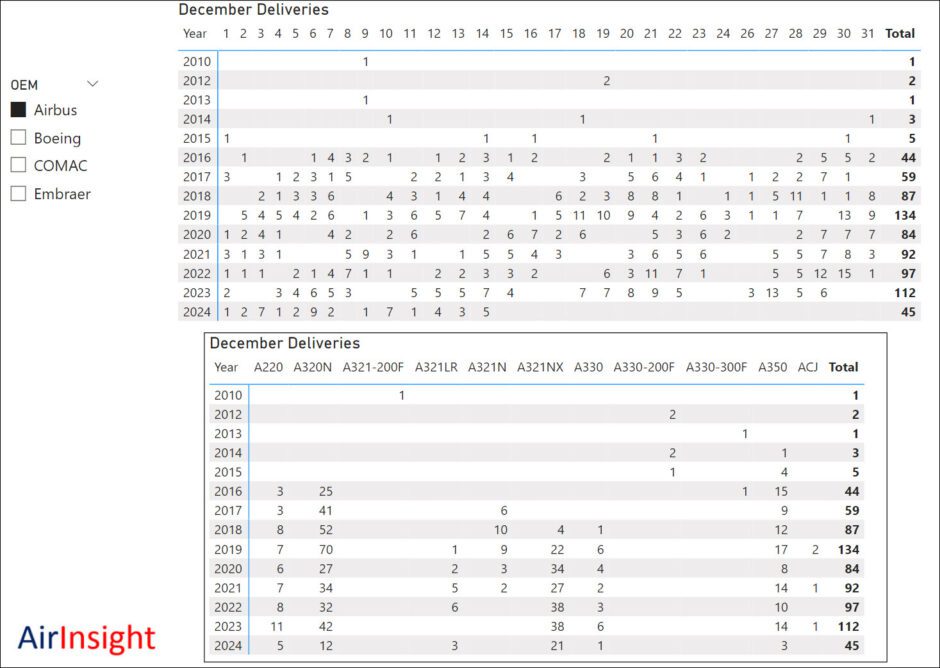

Pay attention to the last column in the upper chart, which shows the sum of deliveries for the year. It’s no surprise that 2019 was the high point.

Airbus aims to deliver 770 in 2024. As of this writing, it has delivered 687. Can It deliver another 83 in two weeks? Notice that Airbus misses deliveries only on December 25. Santa’s Elves don’t work this hard!

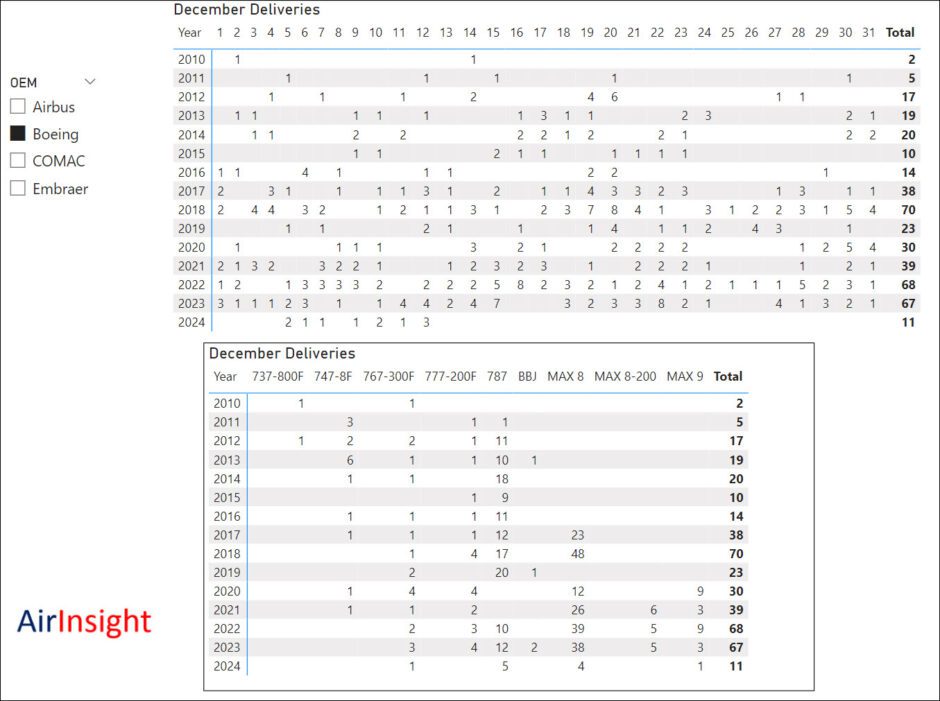

Here’s the same two charts for Boeing.

Boeing has faced a series of disruptive shocks, including groundings, production delays, and, most recently, a strike. As of this writing, Boeing’s 2024 delivery score is 326 against a 415 target. While reaching that target looks unlikely, it is essential to mention that Boeing is recovering from the strike, as evidenced by the rising number of first flights.

It may have been an awful year for Boeing, but 2025 looks much better. For the sake of the entire commercial aviation silo, Boeing’s recovery is crucial. Everyone wants and needs a stable duopoly.

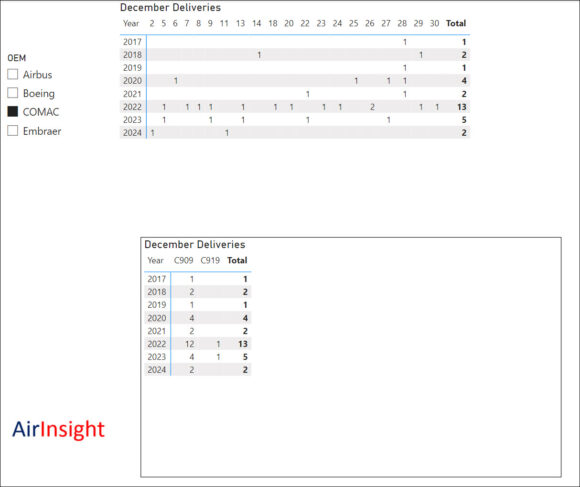

COMAC

COMAC is widening its market view beyond China, opening Singapore and Hong Kong offices. This is good for the industry because this move should encourage COMAC to be more open and forthcoming about their plans.

Notice that the ARJ21 is now named the C909 to be consistent with COMAC’s model naming. The C909 production system is more productive and has a more extensive inventory. COMAC depends on the Western supply chain for significant parts like avionics and engines. As a smaller OEM, it might get slower supply chain deliveries than the duopoly.

This is the OEM everyone is watching because it had a very good 2024. After an arduous recovery from the pandemic and a broken merger with Boeing, EMBRAER has clawed back. Its business jets are market leaders (not reported here), and its defense business is having its best year as the C-390 wins competition after competition.

Unlike the other OEMs, EMBRAER has a monopoly segment; it is the only regional jet supplier that meets Western standards. The ERJ-175 model continues to win new and replacement business in the vital US regional airline market. It has now also started to win ERJ-175 business in Nigeria and India. Both these markets are likely to influence other operators to consider this model.

Although Embraer is a smaller OEM and receives less attention from the supply chain, it has another advantage. EMBRAER is more vertically integrated; it builds its wings and landing gear and develops its (now fifth-generation) fly-by-wire software. Moreover, the company focuses intensely on internal engineering creativity. This IP is then spread across the company’s entire portfolio. EMBRAER’s leadership points to this function as a key driver in its recovery.

While its flagship E2 line continues to seek orders to fill the backlog and get back to pre-pandemic production levels, EMBRAER is being closely watched. This OEM is expected to try to break into the duopoly because it has the engineering talent.

Conclusion

All four OEMs are working through the supply chain fracas. The supply chain suffers from technical challenges among engine makers, for example. Then there is the critical shortage of skilled labor entering the silo. This hunt for talent remains brutal. Aerospace does not look attractive enough to work; for those who find it appealing, Space X is where they want to go.

The OEMs and the entire supply chain must find creative ways to attract the needed talent: the NetZero goal and other fascinating aspects of commercial flight beckon. Fixing the talent shortage will go a long way toward fixing the supply chain.

Views: 376