2024 04 15 182619

The global pandemic and COVID-19’s impact are still with us and have taken multiple forms. But at the heart of the matter is what has been described as the great retirement. As demand fell during the pandemic, companies trimmed costs, and many offered buyouts to senior employees.

This was particularly true for the supply chain in the aviation industry as airline traffic fell precipitously to almost nothing, factories closed, and demand for parts faltered. While the shutdowns likely saved lives during the initial outbreak, the economic impacts of those shutdowns, which brought some supplier closures, are still being felt. Let’s look at some of the reasons why.

First, the loss of employees during the pandemic was significant in quantity and mix. The employees typically bought out and provided early retirement were the most senior and knowledgeable. These people understood how to solve problems and work through difficulties as production rates increased. Without them, suppliers had difficulty in ramping up.

The loss of employees could not be quickly replaced. It often takes two to five years for a production employee in aerospace to learn difficult tasks and gain the experience necessary to work unsupervised on components critical to flight safety. As the OEMs plan to ramp up production, suppliers need to anticipate those requirements and hire and train people in anticipation of future needs. Unfortunately, the major OEMs didn’t expect the robust traffic return, nor factor labor requirements into procurement processes, placing the supply chain “behind the power curve” when it comes to rate increases.

Airbus recognized the depth of the problem within its workforce and is now hiring employees for a new final assembly facility that will come online in two to three years. Those employees need training in production and safety processes and must be ready to work at the new facility once it opens. Airbus is preparing its facility for its rate increase, but suppliers are not in the same financial position as Airbus.

Suppose suppliers cannot increase their employment levels before the proposed rate increases. In that case, there will likely be shortfalls in Airbus’ attempt to reach 75 narrow-body aircraft per month in 2026, and Boeing plans to move to 50 plus over the same time frame, FAA permitting.

Given the condition of the supply chain, we don’t see either of those rates easily being met by 2026. All it takes is one component out of many thousands not being available to stop the production lines at the OEMs. That remains a strong likelihood as suppliers struggle with production ramp-ups.

The problem is complicated at Boeing, where the FAA has limited rates. Boeing is taking inventory at a rate of 38 per month. Still, in 2024, it produced only 36 newly built MAX aircraft during the first quarter, with the majority of sales coming from inventoried aircraft built for Chinese and Indian carriers some time ago. Eventually, if the FAA-restricted rates continue, this will hurt the supply chain, as neither Boeing nor Airbus can produce at their desired rates. The net result is that despite record backlogs and demand, the OEMs may need to restrict deliveries.

When will things stabilize? The correct answer is when the last supplier stabilizes and delivers enough product on time and budget to meet the ramp-up objectives. Airbus and Boeing have each focused their efforts on solving supply chain problems. At Airbus, their focus has been capacity. For Boeing, both capacity and quality issues have emerged, given recent problems with Spirit AeroSystems quality problems on 737 MAX fuselages and the multiple fuselage suppliers for the 787, with pieces that don’t fit together within tolerances.

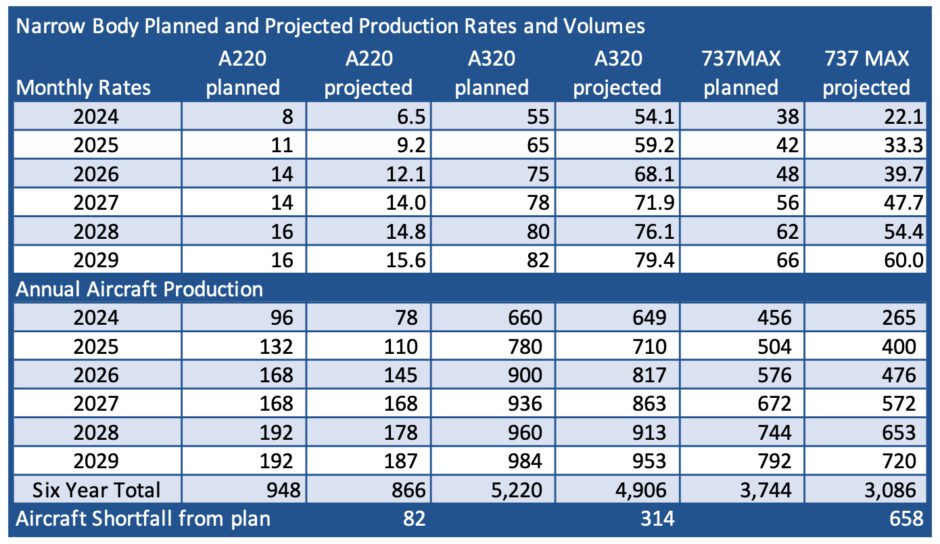

Our projections indicate that the Airbus supply chain will be near normal by the second half 2025. The Boeing supply chain will be normal in capacity by the first half of 2026, with no estimate of how quickly the quality issues will be solved. We believe actual production rates will be slightly lower than projected ramp-up rates, as follows:

With a projected shortfall of 1,054 aircraft over the next six years, the airline industry will be constrained, leading to higher fares and load factors.

The Bottom Line

Who wins? The leasing companies that have secured large delivery positions for popular aircraft, including the very popular A321neo, will be winners as they have assets in high demand and could command high lease rates because of that demand. With new aircraft replacing older aircraft now delayed, the older aircraft will need to remain in service. MROs and aftermarket parts overhaulers will find their product in strong demand.

Who loses? Airlines with large delivery positions for the MAX won’t likely see the model they desire anytime soon – the MAX 7 for Southwest and MAX 10 for United, for example. Delays in deliveries will impact route structures and the airlines’ ability to grow and compete in new markets.

Of course, the beleaguered supply chain also loses, as parts for new aircraft will not be delivered at planned rates. In addition, the deferred expected growth in MRO from aircraft that should have been in service but are now delayed will also impact the demand for spare parts.

Being a supplier is tough. Being a supplier that has survived the up-and-down volumes post-pandemic and is looking at high potential variability in future production is even tougher. While we expect the industry to rebound strongly, the timing of that rebound remains uncertain, with our latest forecast subject to change. However, events in this industry tend not to go as planned, and our expectations for the supply chain from the continuing aircraft shortfall will be meaningful.

Views: 17